Tracks on 10th

The same goes for the city’s two major hospitals, according to representatives from St.

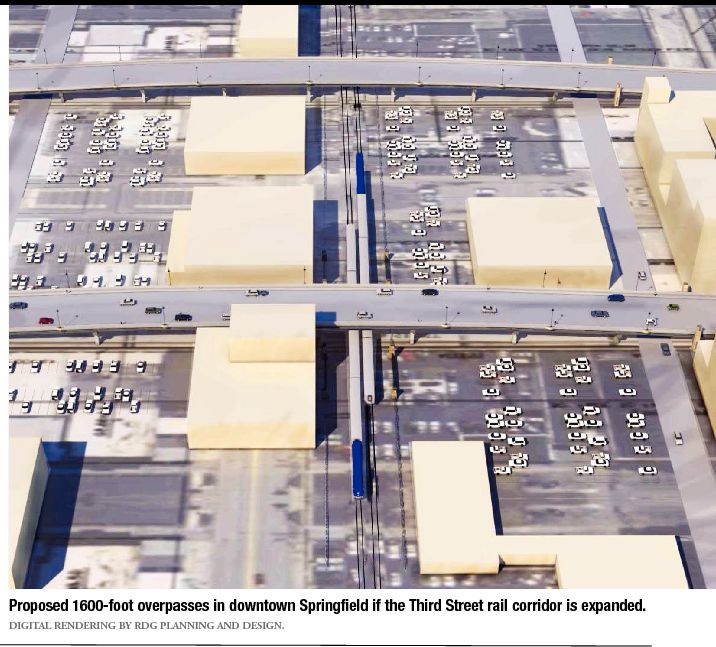

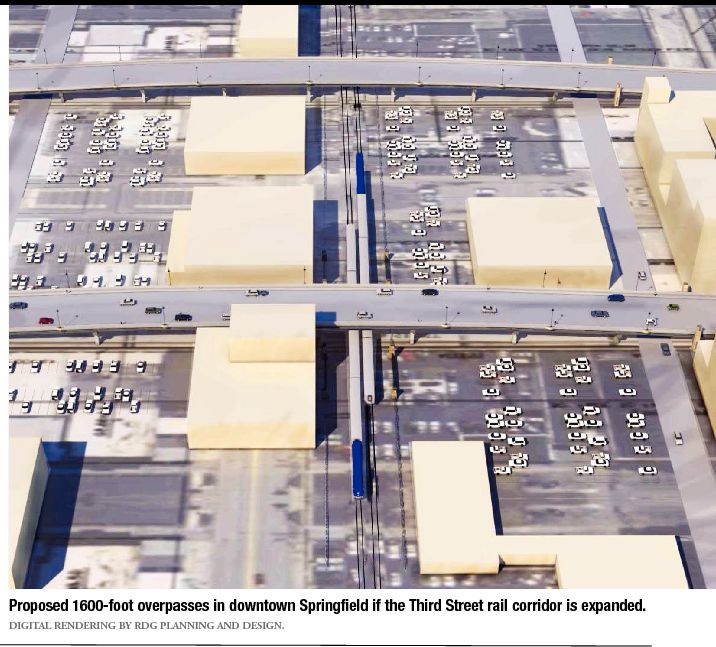

John’s Hospital, Memorial Hospital and the Mid-Illinois Medical District. Delicate equipment used in the hospitals could be damaged or miscalibrated by train vibrations, they say, and traffic delays due to trains could impede access to the hospitals by emergency vehicles. Downtown businesses such as Isringhausen Imports car dealership say consolidation on 10th Street is preferable to double-tracking Third Street because the latter option would partly surround their businesses with overpass ramps, greatly reducing customer access.

Springfield Ward 2 Alderman Gail Simpson says she favors consolidating all rail traffic on 10th Street, pointing to redevelopment possibilities that could accompany an expansion of that corridor and the opportunity to eliminate the 19th Street rail corridor. The study group has projected a swath of new affordable housing, walkways and businesses along an expanded 10th Street corridor. A proposed transportation hub combining a rail station with buses and taxis has been on the drawing board for years.

“It is imperative that a multi-modal transport center be put on 10th Street to spur economic and business development,” Simpson says. “It will bring jobs and, I believe, a renewal to east Springfield.”

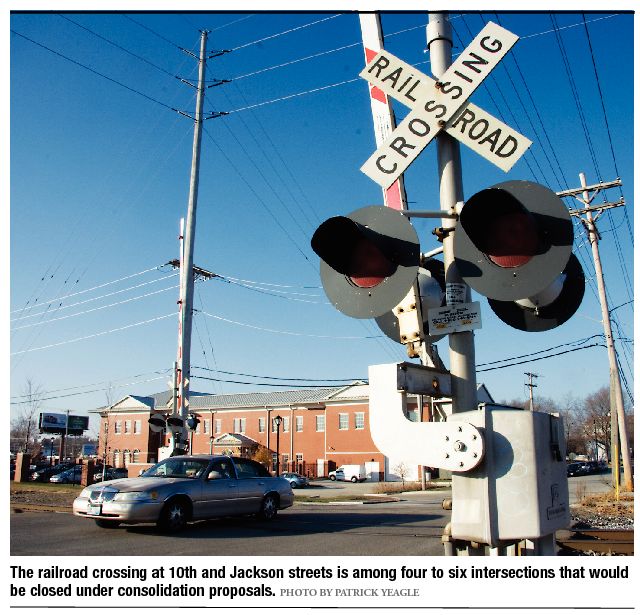

Challenges Despite the benefits offered by consolidating the city’s rail corridors, the idea also presents important challenges. Because consolidation would double the width of the 10th Street rail corridor, that option would result in the highest number of residential and commercial displacements of any option. The rail study group proj ects that full consolidation would require demolishing between 200 and 250 residential buildings and moving those residents elsewhere. That’s in addition to more than 50 projected commercial displacements under the full consolidation proposals.

The expanded right-of-way would also run into the historic Lincoln Depot, the building at which Abraham Lincoln gave his farewell address in 1861 when leaving Springfield to assume the presidency. However, the Tenth Street corridor touches fewer historic structures than the Third Street corridor, the study group notes, adding that there is no talk of demolishing any historic structures. Additionally, the consolidation proposals call for rerouting part of the 10th Street tracks through what is currently the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency headquarters on North Grand Avenue, meaning that building would likely be demolished.

The initial cost of full consolidation is significantly higher than most other proposals, with an estimated cost of $427 million for Alternative 3A and $516 million for Alternative 3B. By comparison, the cheapest option – dou ble-tracking

Third Street with no new grade separations – would cost an estimated $99 million.

However, taking into account long-term savings due to reduced delays, crashes, maintenance, fuel and emissions over the 75-year lifespan of the project, the $158-$185 million net cost of full consolidation would actually be lower than the $205-$260 million net cost of double-tracking Third Street. Partial consolidation, which would require moving Third Street rails to 10th Street and leaving 19th Street in place, would have the lowest net cost, at around $85 million.

Perhaps the most important challenge to consolidation on Tenth Street is the concerns of east side residents that consolidation would isolate them from the rest of the city. Teresa Haley, president-elect of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) in Springfield, says more trains on 10th Street would devalue east side properties, cut off residents from emergency services and cause unnecessary delays in transportation. She also cites concerns about traffic crashes, derailment dangers, train noise and vibration damage to east side homes. Haley says NAACP has done studies of other areas with major rail projects and

has seen low-income areas receiving lowerquality sound barriers and safety features. Even with assurances of full grade-separation at all train crossings between North Grand Avenue and Stanford Avenue under one of the consolidation options, Haley is unconvinced.

“That doesn’t alleviate our concerns that disparity will still be there,” she says. “There will still be a great division.”

Prospects for redevelopment, Haley says, are likely to be forgotten, as past projects on the east side – including a tax increment finance district and job development programs – have failed to produce promised developments. “You don’t see any minorities, contractors or subcontractors, working on any repairs around here,” she says, with noticeable frustration in her voice. “When the city was doing last-minute repairs to make sure the streets were handicap-accessible, there were no blacks out there doing repairs. Hell, I could hold a sign. What are the true qualifications to get these people employed?” Leroy Jordan, president of the Randall Court Neighborhood Association on Springfield’s east side, says several 10th Street redevelopment concepts put forth by the rail study group are “designed to show the best picture” of what could happen there, but are “kind of misleading” because there is no money allocated for such projects.

Jordan is also chair of the Rail Issue Task Force through the Springfield-based Faith Coalition for the Common Good, which is focused on reaching an agreement with the city and state to ensure a proportionate amount of jobs created by the rail project go to minorities and women.

“In places where they have a crossing already, the company doing the asphalt work is from St. Louis,” Jordan says, referring to railroad repairs underway now. “We have at least five or six asphalt companies here in

Springfield. If the federal government is expecting us to have 30 percent minorities and 20 percent women working on the expansion, and our companies are not there yet, we are already losing out. Maybe it’s our fault for not coming together to deal with being behind. We can’t blame them for what we don’t do.

“I have a passion about this,” he continues.

“I want this to be different than the previous railroad relocation initiatives, but thus far, it seems to be the same old song. Let us continue to pray for hope – hope that we can do better, because we really do deserve better.”

Ald. Simpson, who is in favor of consolidation on 10th Street, says she will work to assuage concerns about that option.

“I understand those concerns,” she says, adding that she will “stay vigilant” in talking to development authorities about what the east side wants.

“The only reason I am promoting this as a viable option is that it will allow for economic and business development along 11th Street, which encompasses the 10th Street rail,” she says. “I’m going to continue to promote that, because I think it’s important that entities in this city understand that we can’t keep developing west. You’ve got to, at some point, develop in the center of the city.”

Lee Hubbard, speaking in front of the Lincoln Colored Home he is helping to restore, says consolidation would be beneficial for the east side.

“We’re losing our identity and our structures,” Hubbard says. “Nothing has really changed here in a number of years, but we have hope. There’s a lot of good people in Springfield, willing people. We’ve been here a long time, and we’re going to be here a long time. We don’t want to move out to the west side. There’s still a lot that can be done here.”

Contact Patrick Yeagle at [email protected].