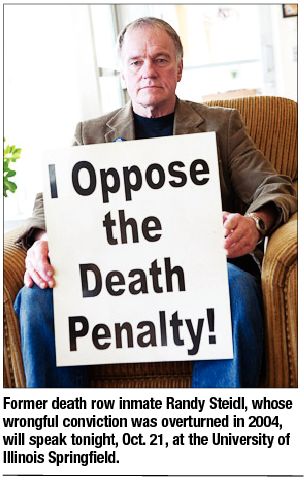

Former death row inmate speaks out

Coalition plans major push to abolish death penalty CRIME | Rachel Wells

While sitting on death row for 12 years, Randy Steidl wasn’t against capital punishment. Not in the general, philosophical sense.

“I came from a conservative farm family,” he says, explaining his position on the death penalty when he was arrested for murder in 1986 at the age of 35. “I believed in the system,” he said in a phone interview with Illinois Times.

Steidl will be speaking publicly as part of the “Beyond Repair Tour” which stops tonight, Oct. 21, at 7 p.m. at the University of Illinois Springfield in the Public Affairs Center, Conference Room G. The tour is an initiative of the Illinois Coalition to Abolish the Death Penalty, which is planning a major push in the legislature during this fall’s veto session.

Steidl was convicted and placed on death row until 1999, when it was discovered that his attorney wasn’t prepared for his previous sentencing. Re-sentenced to life without parole, Steidl came to understand the emotions visible on the faces of the prisoners he’d watched walk to their deaths “with their heads held high like they were going to a family reunion.” He soon realized that those men were being released after years in a cage. “Had they rolled that gurney by, I would have buckled myself in,” Steidl says of the misery of an endless prison sentence. “You really want to punish somebody, you keep them in a cage for the rest of their life so they think about the crimes they committed.”

More importantly though, life without parole means the state isn’t putting to death an innocent person. Knowing he had more time to appeal his case was the only solace for Steidl, whose wrongful conviction was finally over turned in 2004. He’s one of 20 innocent inmates placed on death row in Illinois since 1977. “It’s just an error rate that’s too great to continue this type of punishment,” he says of the death penalty. “We cannot guarantee that an innocent person will not end up on death row.”

While capital punishment is an issue of morality, it’s also an issue of economics, says ICADP director Jeremy Schroeder. According to ICADP, the death penalty costs the state $12 million every year. “For a lot of people, the death penalty is not a huge issue,” Schroeder says, describing Illinoisans who are out of work. “But when they find out we’ve been spending tens of millions of dollars just to have this on the books, it becomes one.”

While convicted criminals can still be handed death sentences in Illinois, those punishments aren’t currently carried out. Gov.

George Ryan in 2000 placed a moratorium on all such punishments, citing flaws in the system and Illinois’ high wrongful convictions rate. Ryan also commuted the death sentences of more than 160 inmates in 2003. Since that time, 15 more convicted criminals have been sentenced to death.

Schroeder says the upcoming veto session is an ideal time for lawmakers to address the issue, in part because the Nov. 2 election will have passed. His group is planning a lobby day at the Capitol on Nov. 16, the first day of the veto session.

Neither Democratic incumbent Gov. Pat Quinn nor Republican Bill Brady oppose the death penalty, but only Brady has said he’ll lift the moratorium. Green Party candidate Rich Whitney favors abolishing capital punishment altogether.

“I think it’s something we’re still working with both candidates on, letting them know about the truth on the death penalty,” Schroeder says. Even with reforms, the system is too costly, he says. “We need to grow up a little bit and admit that if we do continue to tinker with the death penalty it’s going to cost hundreds of millions of dollars we don’t have.”

UIS’s student Amnesty International, a human rights group, is hosting the Oct. 21 talk. Alfred Komolafe, founding president of the campus organization, says the death penalty and its flaws as a human-controlled system are important human rights issues that most don’t know enough about. He hopes Steidl’s talk will encourage students and community members to contact their legislators. “Even though it might not affect them directly today, tomorrow it might affect them, or their family or somebody they know,” Komolafe says. “Just like today I am fighting for somebody, tomorrow somebody might be fighting for me.”

Contact Rachel Wells at [email protected].