Lincoln didn’t sleep here

Setting the record straight on Abraham Lincoln’s ties to Edwards Place HISTORY | Erika Holst

No, Lincoln didn’t sleep here. And, in the case of Edwards Place, the Springfield Art Association’s antebellum Italianate mansion, Lincoln didn’t court here. Abraham Lincoln actually called on Mary Todd at the home of her brother-in-law, Ninian W. Edwards, and married her there on Nov. 4, 1842. That house used to stand on South Second Street before it was torn down in 1918 to make way for the building later named the Howlett Building.

The big pink house on North Fourth Street that now bears the name Edwards Place was the home of Ninian’s brother, Benjamin. And while it might not be the place where Lincoln courted Mary Todd, it does contain the sofa on which they sat during their courtship. Dubbed the “courting couch,” it belonged to Ninian and Elizabeth Edwards and was one of a pair that stood in their double parlors when Abraham Lincoln came to call. The courting couch is just one attraction of a house that has a rich and interesting history – including ties to Abraham Lincoln – all its own.

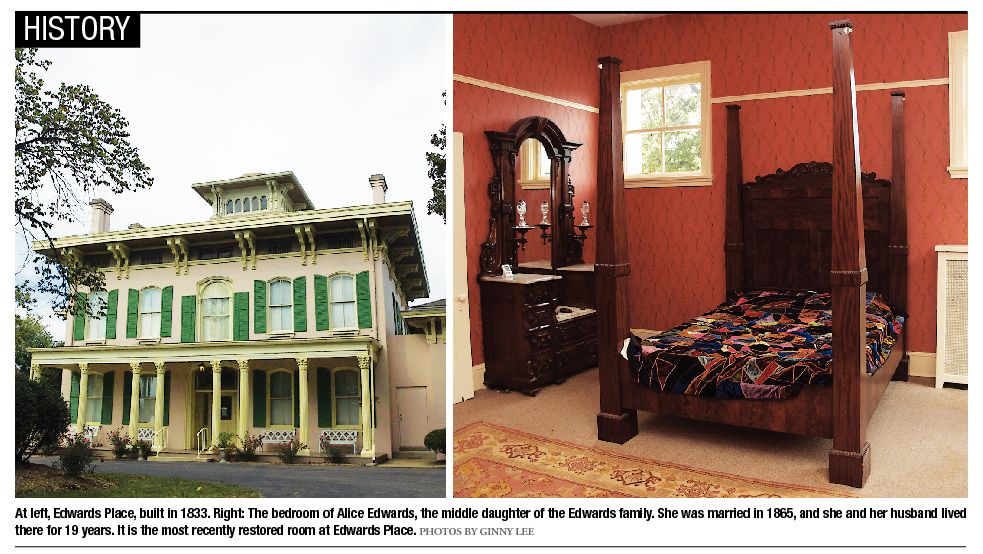

Edwards Place holds the distinction of being the oldest house in Springfield on its original foundation. It was built in 1833 for Dr. Thomas Houghan. In 1843, Houghan sold the story-and-a-half brick house and 15 acres to Benjamin Edwards for $4,000. Benjamin made a $50,000 renovation to the house around 1857, enlarging it to its present 15 rooms.

Benjamin came from a prominent family.

His father, Ninian, was territorial governor, senator, and governor of Illinois. His older brother, Albert Gallatin, was a merchant in St. Louis who went on to found the brokerage firm of A. G. Edwards. And his oldest brother, Ninian W., was a state politician and Springfield’s social leader.

It was through his brother Ninian that Benjamin and Helen Edwards first met Mary Todd. Helen later recalled, “She greeted me with such warmth of manner…saying she knew we would be great friends and I must call her Mary. This bond of friendship was continued to the end of her life.”

That bond only grew tighter when Mary married Abraham Lincoln. Benjamin and Helen Edwards were among the small number of guests who attended the Lincoln wedding, and Helen was one of the women who helped then seven-months-pregnant Elizabeth Todd Edwards prepare the wedding supper for her sister, Mary.

To modern eyes, Abraham Lincoln and Benjamin Edwards were only distantly connected through marriage: Lincoln’s wife’s sister was married to Benjamin’s brother. Yet in Lincoln’s view, according to his friend David Davis, “Ben was in the family.”

Benjamin and Lincoln moved in the same professional circles. Benjamin, like Lincoln, was an attorney. In 1843 he formed a partnership with John T. Stuart, who had been Lincoln’s partner until 1841. Lincoln and Benjamin would meet in the courtroom on more than 400 occasions, either as co-counsel or opposing attorneys. Both served as defense attorneys during the Anderson murder trial, made famous in Julie Fenster’s The Case of Abraham Lincoln: A Story of Adultery, Murder, and the Making of a Great President.

The Edwardses and Lincolns also moved in the same social circles and were almost certainly guests at each other’s houses. Both families were known to host parties during the winter when the legislature was in session, Springfield’s high social season. Among the invitations received by Springfield’s prominent

families in February of 1857 were one in Benjamin’s hand that read “Mr & Mrs. B. S. Edwards will be pleased to see you on Wedn: Eve. Feb. 4 1857 at 8 o’clock” and one in Lincoln’s hand that read “Mr. & Mrs. Lincoln will be pleased to see you Thursday evening Feb. 5. at 8. o’clock.” The Edwardses and Lincolns likely went to each other’s parties; a few weeks later Mary Lincoln wrote to her sister, “Within the last three weeks, there has been a party, almost every night.”

The one area where Lincoln and Edwards did not see eye to eye was politics. Although both men were Whigs until the party dissolved in the mid-1850s, Lincoln then cast his lot with the Republicans, and Edwards became a Democrat. During the 1858 contest for Senate, Stephen A. Douglas held a political rally at Edwards Place, while Lincoln addressed his own supporters later that day in the Capitol Building.

Today Edwards Place is open to the public Tuesdays – Saturdays from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m., with tours being offered on the hour. The house interprets mid-to-upper-class social and domestic life of 19th century Springfield, giving a window into the lifestyle that Lincoln aspired to and eventually attained. Visitors will see the parlors where Lincoln and other important men of his time were entertained; portraits of prominent 19th century Springfield citizens; a collection of stunning antique furnishings with ties to Springfield’s best-known early families, and, of course, the courting couch.

Erika Holst is curator of collections for the Springfield Art Association and author of Wicked Springfield: Crime, Corruption & Scandal During the Lincoln Era.