STORM OVER SEWERS

Because the overflows potentially contribute to pollution problems, the SMSD is performing a three-year study, as mandated by the EPA. Should the 2012 study results show that the Springfield-area sends too much overflow into the waterways, corrective action of some sort will be necessary.

Although reluctant to look so far ahead, both Norris and SMSD director and engineer Gregg Humphrey say combined sewer separation could become part of the long-term control plan that will be formed based on the study. But even with sewer separation, residents’ water issues wouldn’t be fully resolved.

“You still get flooding with a 100-year event because sewers are sized for five- or ten-year events,” Norris says. Because sanitary sewers would be separate from storm sewers, backups into homes would be less likely, but street flooding would likely remain an issue.

Should the pollution study find a problem with overflows, another potential corrective action that could be prescribed is additional treatment capacity, a project the SMSD is already undertaking. A new plant expected to be complete around February 2012 will increase overall capacity by 30 million gallons of water per day to 313 million gallons per day. A rehabilitation project at another plant, expected to be complete by 2017, will increase capacity to 328 million gallons per day. Still, exceptionally wet years like this year and last year will likely exceed the district’s treatment capacity.

“You can’t design for the ultimate Mother Nature’s going to throw at you because no one knows what that is,” Humphrey says. “You build what’s economically feasible.”

The increased capacity could ease in-town flooding issues, but not much. The SMSD might have more capacity, but without more capacity added to the collection system, which is the city’s responsibility, treatment plant upgrades won’t do much to help flooding issues, Humphrey says.

Concrete conveyer Logue says that rather than collecting all of the excess water in traditional sewer pipes and sending it off for treatment, there’s another, much more basic defense that could help Springfield’s flooding situation.

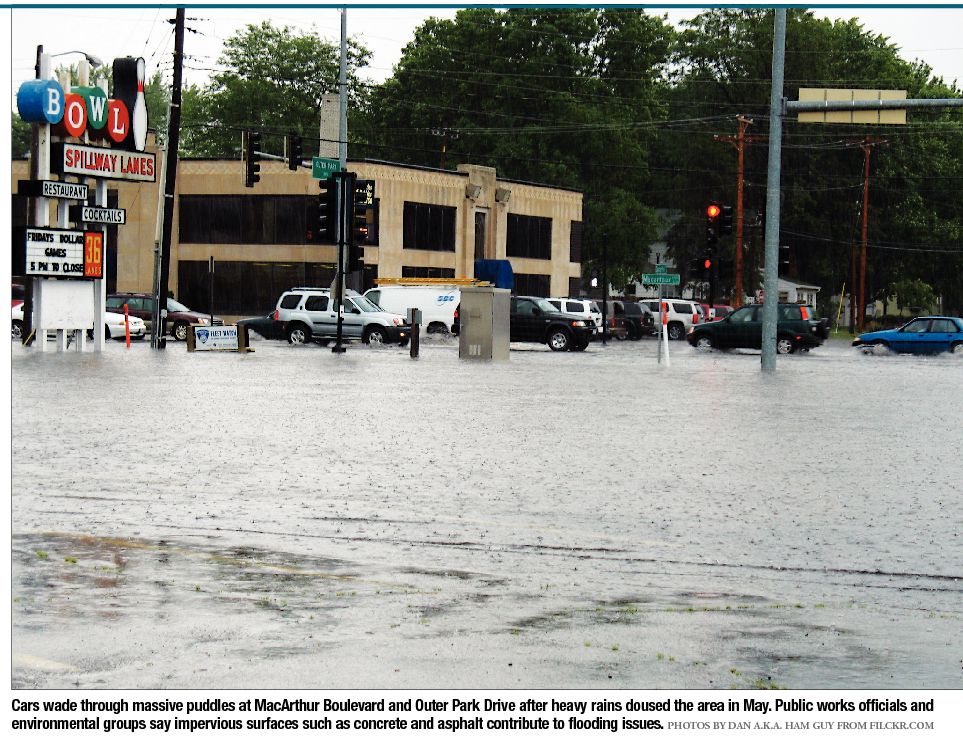

“The obvious problem is impervious surfaces,” she says. “When you have a surface that water doesn’t sink into, then obviously you have a problem with flooding.”

Humphrey and Wallner agree that the blanket of concrete and asphalt that is downtown Springfield contributes to flooding problems. As the rain falls, it travels across those surfaces – parking lots, roads and sidewalks – until it finds a low spot.

Other Illinois cities are already testing multiple approaches that would help water penetrate the ground where it lands instead of moving away and pooling in low spots ripe for flooding, Logue says. Permeable pavement, green roofs, rain gardens, wetlands and rain barrels could all help mitigate flooding issues. “Basically, it’s slowing the whole process down and that’s the point. That’s the problem, it [the rain] just comes down too fast,” Logue says.

She says Chicago is a good example of a city embracing alternative infrastructure. Already, the Windy City is experimenting with permeable pavement through its green alleys program. According to Chicago’s transportation department, between 2006 and 2009 the city installed more than 100 green alleys, paved with asphalt and concrete that are designed to let storm water pass through the pavement and drain into the ground. The system alleviates additional pressure on the sewer system while also recharging groundwater supplies and filtering pollution.

Norris, Springfield’s public works director, agrees the alternatives Logue suggests would help curb some of the

city’s problems. “Any of the green infrastructure – rain gardens,

bio-swales, that kind of stuff, helps to dissipate storm water before it

gets to the system and, frankly, it’s a wonderful thing,” he says.