Arts, Science and Technology Come Together for Covid-19

A fairly universal experience when people heard their workplaces, houses of worship, restaurants and every other kind of business or organization were shut down because of health mandates.

A fairly universal experience when people heard their workplaces, houses of worship, restaurants and every other kind of business or organization were shut down because of health mandates.

People suddenly had plenty of time, but what to do with it?

One such person was Eric Hess, one of the glass artists at Sanctuary Art Glass near downtown Shreveport. He and his partner in glass, Michelle Pennington, were just two more citizens cast adrift on the shores of idleness. Hess was noodling around Facebook when something caught his eye.

A friend in Colorado had begun making glass splitters, sort of a crystalline “Y” shaped contraption, that could let the output of one medical ventilator be shared by two patients. Colorado, like Shreveport and most of the rest of the world, was experiencing a shortage of ventilators where they were needed. This seemed like a good, short-term solution, so Hess jumped on board the glassmaking bandwagon.

Hess, if you are unfamiliar, is a high-octane, Type A personality. This project was just up the bored artisan’s alley. It wasn’t long before he had jumped ahead. “I got on a nationwide initiative with five glass artists from around the country to make these available for the hospitals,” he said. They studied the medical requirements of the splitters and soon were taking their first steps in producing them.

Before long, Hess and his colleagues had begun turning out prototypes and testing them at hospitals; one went to West Jefferson Hospital in New Orleans.

It wasn't long after that that an acquaintance working in a local hospital shared that masks were scarce at her facility, but what were really needed were full-face shields. Those would protect health-care workers who were in close contact with patients with respiratory issues.

With an extensive background in fundraising, Hess started looking for donors to purchase the needed personal protective equipment (PPE), but it didn't take long to find out such gear was as scarce as toilet paper. More searching showed that the National Institute of Health had published a design that was 3D printer-compatible. He called another acquaintance, Matt Hopper, who owns Ark- La-Tex 3D Technology Company and works as an engineer at Libby Glass.

"We've got a small 3D printing company with four or five machines," Hopper said, "and we designed a really large 3D printer several years ago, and all of this stuff has been on display at SciPort for the last few months.

“This all started about three weeks ago. Eric gave me a call. He said, ‘I’ve got a couple of folks here from LSU Medical Center that are seeing these 3D printer face shields, and they're saying that they could use something like that. Is this something you could do?' I said, sure.

"So, we made a few samples, and [Eric] took those to the hospital. The next day he calls me back and says, 'Matt, they want a thousand.' And I said, 'Whoa!'" At that point, Hess said, “We realized this was much bigger than we thought.”

Stunned,

but undaunted, Hopper rounded up his printing equipment and started

printing the plastic forms. They then got with LSU- Shreveport and

Bossier Parish Community College “because we knew they had technology

labs,” according to Hess.

"For

about 16 years, I was an adjunct instructor teaching 3D drafting and

design and manufacturing at BPCC," Hopper explained. "I knew they had

eight to 10 printers there." He asked if the college would come on

board; they agreed, and soon were printing the headbands.

Dr.

Julie Lessiter is the vice-chancellor of strategic initiative at LSU in

Shreveport. She was contacted by Shreveport Economic Development's

Brandon Fail, whom Hess had reached out to about the collaboration. Hess

put her in touch with Hopper.

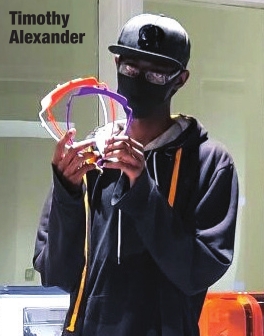

SWEPCO to assist in the endeavor. Two students who had 3D experience were also recruited along with a faculty supervisor.

“We

went in and built up a 3D print lab. Everything we do is with

emergent-tech. We have this 10,000-square-foot space that used to be our

bookstore that we’ve converted into what we’re calling a Cyber

Collaboratory. That’s going to open this fall.”

"It

takes about an hour to print one headband, and we have about 12

printers going right now. We stood up this lab thinking we'll be

printing for about four weeks, which is why we're really grateful for

the external funding from SWEPCO to cover the cost of materials we're

using," she said. Their current output is about 100 headbands a day.

After

LSU joined the team, Hopper said Demetrius Norman from the Northwest

Louisiana Makerspace called to say they would like to help. Hopper said,

“The next thing you know, Eric calls and says, ‘The mayor wants to have

a meeting.' 'The governor's calling.' 'Somebody from the team of the

mayor of New York is calling saying we'll take as many of these things

as you can make as fast as you can make them.'" Hopper said it takes

20-30 minutes to print the headband piece. They needed to up their game.

“My kitchen table we set up with clamps and boards so we could take

this clear plastic and cut it to size for the front [of the face

shield].”

Looking

for a solution, Hopper called Raytech Industries in Bossier City. He

wanted to know what it would take to create an Line Mold & Die in

Shreveport, heard about the project and got involved as well.

Hopper’s

day job at Libby Glass was furloughed like many others, so Hopper asked

permission from plant management to use the machine shop. The plant

manager not only threw in free use of the shop but supplied a machinist

as well. The mold could be finished before this issue of 318 Forum reaches you.

The

team got a call from the state of Louisiana asking for a request for

quotes for two million units. Hopper told Hess that it would be possible

to produce upwards of 6,000 a day. If demand rose, they could add

additional injection molds at $60,000 to $70,000 each, which Libby is

funding.

At

one point, they were injection mold which could be used to massproduce

“I’ve started calling all the social workers, Once she knew what was

needed, she went to her bosses, who okayed the use of space, which is

currently under construction. They also obtained outside funding from

AEP/ turning out 300 units a day, but they realized the process was too

slow, and as the word spread around a desperate medical community, the

orders began to flood in.

the

headbands, the time-consuming piece of the project. He was told he’d

need a mold designed and manufactured to the right specifications. Paul

Morse, who owns Red [grocery store] cashiers, anyone who is dealing with

the public one on one, hospice workers, home health workers,” Hess

said. "So, we’re

getting these things out as fast as we can to everybody to cover the

community. We’re looking at giving away about 10,000 in the

Shreveport-Bossier City area.”

Hess

and Hopper did a local television news interview and, according to

Hopper, "the next thing we knew, the story had gone all over the

country. I got a call from a gentleman in Houston who works for Curtis

Wagner Plastics. They had started making the clear portion of the face

shields and wanted to know if I was interested. I thought, yeah, I’m

spending hours cutting these things on my kitchen table; yeah, I’m

interested.”

A partnership was hammered out, and the Houston firm began supplying the clear face shield fronts.

The Governor's Procurement Office also sent letters statewide, which has resulted in requests from all over the state.

“We’ve

gone from a 3D printing operation with four or five printers and a

little network with BPCC and LSU-S to a full-on, largescale

manufacturing operation in record time,” Hopper noted.

It’s

not hard to imagine the pathos that this teamwork evokes. “What’s

really touching, I’m getting individual calls. ‘My daughter is a nurse;

can you please give me a shield?’

‘I'm

a hospice worker, I'm 69 years old, and I'm going in to work with

people that tested positive, and I have no protection.’ I have over a

thousand orders from doctors and nurses at hospitals that are saying we

don't have the supplies.”

That

problem is not isolated to Shreveport- Bossier City. A medical

professional in a distant state explained the situation there: "There is

still a drastic shortage of PPE at our hospital. N-95 and surgical

masks are rationed. We were told that a large percentage of the

hospital's stock was stolen in the early days of the pandemic,

presumably by panicked or opportunistic employees.

"Despite

being disposable, we are having to put them in a paper bag and wait

five days before we can use them again, rotating them out. They become

stained and smell, from hours and hours on our faces. Everything we ever

learned about safe PPE use and infection control from our first classes

in nursing school has gone by the wayside. We all know it's wrong, but

acknowledge that we are in crisis-mode, and nothing is best-case

scenario anymore.

“We

received donations of handmade cloth masks for our workers. We were

using them as covers for our surgical masks that we were having to

conserve and re-use, to try and extend their lives by keeping them

clean. Administration has forbidden us from using them.

“I’m

not blaming our hospital system for lacking enough PPE. That’s out of

the hands of most all hospitals. I do, however, resent them limiting

what we are able to do to protect ourselves and give ourselves some

sense of personal security with whatever options we have at our

disposal.”

In

the meantime, Hess has also teamed up with Sunny Gulley and Shreveport

Sews. “We started getting a lot of calls from nursing homes and others

saying they want the fabric masks,” Hess explained. “I got with Sunny

and asked if she could coordinate a citywide effort for fabric masks.

So, we’re getting all the donations for fabrics and thread. Now we’re

supplying to the food bank, nursing homes and others. We’re trying to

meet all those needs also.”

Looking

ahead to the return to normalcy, Hopper said, "What I see after this is

the medical community or the government reevaluating the need for

certain levels of inventory. Especially of items like [PPEs] in

preparation for something like this [pandemic] to happen again. I think

we’ll satisfy this short-term need, but I think there may be more of a

long-term need as organizations re-evaluate their demand for some of

these inventories.”

Hess

and Pennington have a more artistic future vision. “Once this is over,

that’s it. We will be back to glass. We started with the glass

splitters. We just couldn’t say no. If there’s a way anybody in the

community can help anybody else, I think you should try whatever you can

to get us all through this. We want to go back to being glass artists

and producing beautiful glass and having classes and having outreach in

the community.”

Necessity

is the mother of invention, or so said Plato a few thousand years ago;

but it can also be the genesis of an outpouring of community spirit and

cooperation.