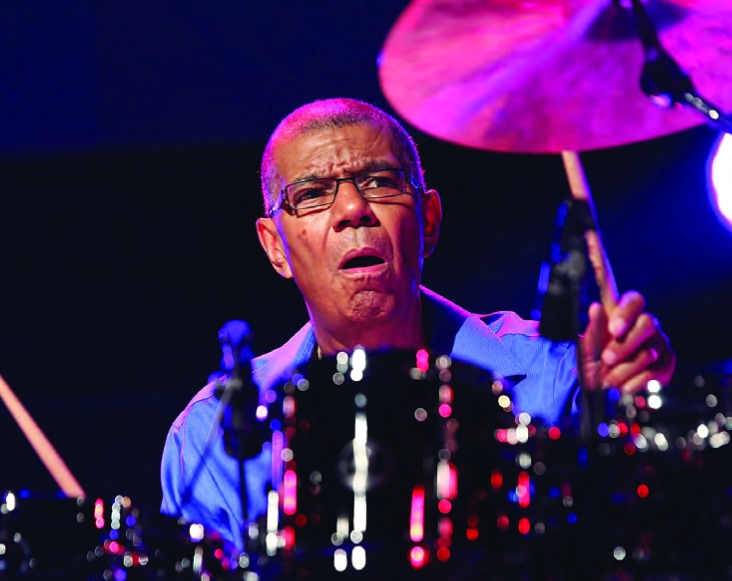

Jack DeJohnette was a six-time Grammy nominee and a two-time Grammy winner.

National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Master and iconic light bearer Jack De- Johnette died Oct. 26 at the age of 83. He had developed a personal style that helped him to be affectionately known as just “Jack.”

To be recognizable is a special characteristic in a musical genre that has no boundaries. Jazz music quickly became the way I wanted to translate how I would tell my stories. As a drummer, there were masters who made indelible influences on my approach direction. At 17, I heard a recording by Miles Davis named “Seven Steps To Heaven.” On the recording was a 17-year-old drummer by the name of Tony Williams and the path was set.

I knew what I wanted to do. So how was I gonna do this?

I started to listen to all of the different styles of music as I could to lead me to Miles. My dad being a huge jazz fan would take me with him to sit in at clubs, to show off his son he thought had talent. On our journey that would include late nights with early-morning work and school wake-ups, I got a call to play with the legendary jazz saxophonist Jackie McLean. My dad drives me from Jamaica, Queens to Harlem jazz club the Gold Lounge. I go on stage to meet for the first time Jackie McLean, Woody Shaw, Harold Mabern and Scotty Holt.

This was a kind of baptism by fire. I survived and then got an opportunity to meet Jack for the first time, because being a drummer and pianist, Jack sat in and played melodica while I

played drums. This situation in itself is unique. The first time I meet

him, I’m not watching him play, I’m playing with him. So, now the talk

is there’s this young kid that is a teenager playing with Jackie McLean

and like young Tony Williams and Jack DeJohnette, I guess he will play

with Miles next.

In

retrospect, the music was now starting to change, and jazz icons are now

starting to translate their musical directions to include more

contemporary rhythms and attitudes. Both Tony Williams and Jack

DeJohnette had been influencing how the new musical directions were

moving, especially jazz Tony with Miles, Jack with Charles Lloyd. John

Coltrane had put a major dent in the new musical direction with his

quartet of McCoy Tyner, Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. There

was this new avant garde tinge influencing jazz along with rock. In the

neighborhood, either Miles or ’Trane had the direction of preference for

young drummers, which meant Tony or Elvin, but now in 1967 Jack along

with Charles Lloyd’s quartet sold a million copies of a jazz album with

“Forest Flower Charles Lloyd at Monterey.” Now Jack was in the flow of

major influencers when it came to drummers.

So

now there have been two times I been with Jack where we’ve played: once

where he sat in with his former employer Jackie Mc- Clean where I

played drums and he played melodica, and at Miles’ house where he played

drums and my work was on snare drum and ride cymbal. Next is Miles’ big

experiment. Teo Macero, Miles’ producer, has me set up right next to

Jack. Now there are two physical drum kits next to each other, this is

physically the closest we’ve been to make music. When everyone arrives,

it becomes real that this is my first time in this situation. I might

have dreamed of this by writing my name on the back of album covers to

see how that would look but I’m in a session with the musicians I read

on albums, Jack DeJohnette and Miles Davis.

I

remember thinking that the music is now starting to change and jazz

icons are now starting to translate their musical directions to include

more contemporary rhythms and attitudes.

The Beatles arrived, rock is starting to become the contemporary musical style

of choice and this is evident by change in Miles’ direction and Charles

Lloyd’s crossover sales. This came to a major crest with 400,000 people

coming to hear a festival of rock, funk and soul music called Woodstock

in upstate New York. Miles was noticing the trends along with others in

the musical community and made a change with his music and recorded “In a

Silent Way,” which was a drastic change for him. Adding guitar to his

now working band of keyboardist Chick Corea, bassist Dave Holland,

saxophonist Wayne Shorter, newly acquired drummer Jack DeJohnette, whom

he took from Charles Lloyd, after Tony Williams leaving with a dispute

with Miles. After the release of “In a Silent Way,” Miles was sill eager

to push the direction even more forward and had an idea to expand.

I

play a gig at a club in Jamaica, Queens with bass clarinet player

Bennie Maupin, drummer Rashied Ali and a trumpet player who I had seen

be around Miles in various situations among other musicians. After the

set he says to me, ‘Has Miles ever heard you play?’ I said no, and he

says, ‘I’m gonna tell him about you.’ I said okay. Then I get the phone

call that would change my life. Miles calls and speaks to my mom and

with his raspy voice my mom hands me the phone. Miles tells me to be at

his 77th Street brownstone for a rehearsal. Just bring a snare drum and

ride cymbal. I can’t drive yet so I ask a schoolmate to drive me; he’s

more excited than me. At the rehearsal is Miles, Wayne, Chick, Dave,

Jack and me. We only rehearse the opening of “Bitches’ Brew.” I am not

sure this is actually real or an out-of-body experience. Miles says be

at Columbia 52nd Street Studios at 10 a.m., Aug. 20, 1969.

The

actual physical act of creating music with these 12 stellar musicians

under the direction of Miles Davis changed the face of music for the

next decade. To be able to co-create alongside Jack was special and to

this day continues to be something that I can relive whenever I want. I

can also listen to how what we did shows up in hip-hop, funk, pro and

jazz music today. I feel so honored to have been asked to be a part of

that special group, including Jack and I, that helped Miles change music

again.

Lenny White is a four-time Grammy Award winner and was part of the group, Return to Forever.