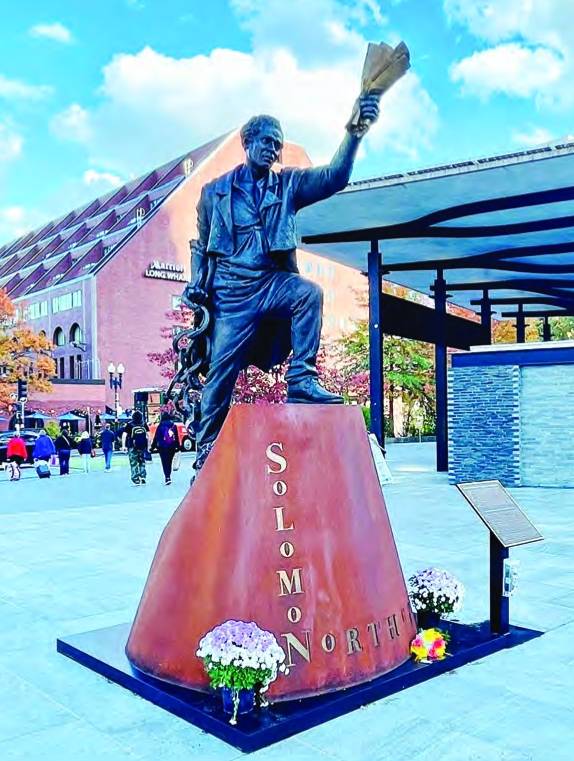

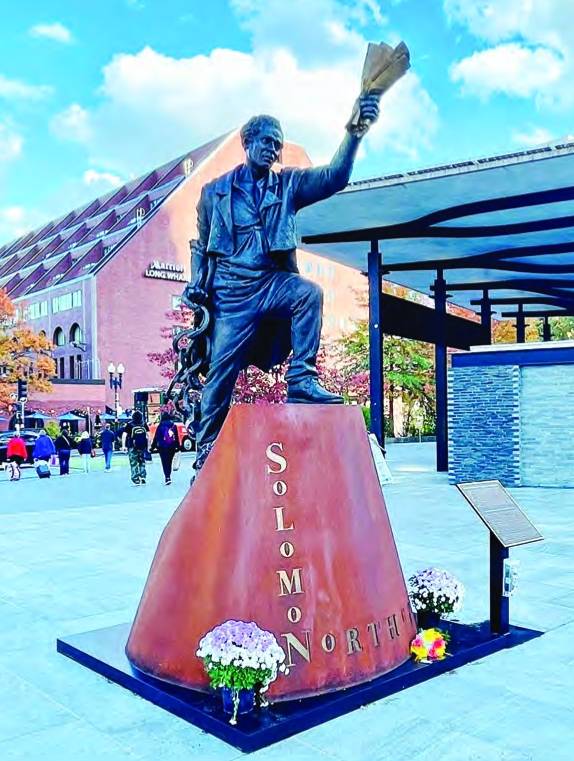

The “Hope Out of Darkness” bronze statue at the Boston Harbor Islands Pavilion. The statue will be on view through December.

The “Hope Out of Darkness” bronze statue at the Boston Harbor Islands Pavilion. The statue will be on view through December.

On the Rose Kennedy Greenway near the Boston Harbor Islands Welcome Pavillion stands a tall bronze statue of a man whose eyes bore a story. He steps forward, gazing ahead into the distance with purpose. That man is Solomon Northup, a free Black man from New York who was kidnapped and sold into slavery for 12 years before regaining his freedom, a story best known by his published memoir, “Twelve Years a Slave.”

The statue, titled “Hope Out of Darkness,” was sculpted by Wesley Wofford and is the first statue of Northup to exist, having been commissioned by the Solomon Northup Committee for Commemorative Works.

Boston is only one stop on its tour throughout the states before it will reside at its permanent location in Marksville, La. It will be on display here through December in honor of Northup’s courageous journey, marking 170 years since his visit to Boston.

Standing at 13 feet, the bronze monument tells a story. The papers raised in his hand represent the legal documentation required for a free Black person to travel in the United States at the time. The shackles, 12 chain links long, illustrate the number of years of his enslavement. The last chain link is broken, representing his freedom. His back bears scars from the abuse he suffered, as he stares into the open.

A farmer and musician, Northup is believed to have been born July 10 in 1807 or 1808 to free Black parents in what is now known as Minerva, N.Y. His father, Mintus Solomon was born into slavery before having gained his freedom when his slave holder passed away. While the identity of Northup’s mother is unknown, it is known that he grew up working farmland that his father had owned.

In 1828 he married Anna Hampton. They decided to sell their farm and move to Saratoga Springs, N.Y., with their three children; he worked a number of jobs to support his family. Northup’s life drastically changed in March 1841 when he accepted a job to work as a fiddler, having been told he would travel south with circus performers.

This would lead to him being drugged, kidnapped and taken to Richmond, Va., before being forced onto a boat and shipped to New Orleans where he was sold in a slave market. Over the next 12 long years of his life, Northup experienced the horrific atrocities shared amongst countless enslaved people.

Spending most of these 12 years in the Bayou Boeuf plantation region of central Louisiana’s Red River Valley, Northup prevailed in moments of great peril and abuse. This, however, often resulted in worse actions being taken against him by his enslaver. John M. Tibaut, Northup’s second owner, had an unsuccessful attempt at trying lynch Northup for his resistance to abuse, before he was sold in 1843.

It wasn’t until 1852 that an abolitionist carpenter from Canada, Samuel Bass, visited the farm Northup was forced to work, owned by Edwin Epps. It was in this visit that Northup was able to arrange having letters go to his family and friends in New York to let them know what happened to him. This was the onset of what would lead to his eventual freedom in Marksville, La, on Jan. 4, 1853.

Once returned home to his family, he worked with a local writer, David Wilson, to tell his story in his memoir “Twelve Years a Slave.” The book was popular in its time, having sold 30,000 copies just three years following its release.

Today, most people know Northup’s story through the popular biopic released in 2013, which won multiple Academy Awards and the Golden Globe for Best Motion Picture. A marker sits at the Avoyelles Parish Courthouse, where Northup had secured legal papers attesting that he was a free man.

It was through this marker that Marksville local Larry Jorgensen discovered Northup’s story.

Jorgensen is a seasoned journalist, having spent his early career in the radio and TV news industry and working as assistant news director at the NBC station in Green Bay, Wis. Since he has gotten older, he shifted from journalistic work to becoming a nonfiction author, writing books about a number of historical events that fascinated him.

Jorgensen recalled walking around his neighborhood in the Marksville area, having seen historical markers that sparked his interest. What started as “an old news dog curiosity,” as Jorgensen described it, soon turned into a full-fledged dive into researching Northup’s story.

“I’ve been doing a lot of research on it, places that he’d been.

I had written about them, and for no particular reason other than I was fascinated by it,” he said. Jorgensen spent his time visiting the places throughout Marksville where he knew Northup had been to fully piece together this story of resilience. He spent two years looking into Solomon’s story, until one night.

“I’m laying there in bed on Sunday night, and I’m watching the Academy Awards, and guess what? ‘Twelve Years a Slave’ wins the Academy Awards. I couldn’t believe it.” Jorgensen said he then hopped out of bed and ran to his computer where he stored two years’ worth of research, and the next morning he connected with his local newspaper to pitch a story.

Since then, and since hearing about the statue of Northup, Jorgensen has been following it from his home in the Marksville area. Conducting interviews and contacting as many people as he can connected to the sculpture, he hopes to finish his book detailing Northup’s story by the end of January.

“The sites were selected, let’s see, because of his experience that he had as a free man, and the tour is to honor his legacy as his inalienable rights of life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness for all people,” said Jorgensen.

The statue has been on display at many places, including Wallace and Alexandria, La.; and Haverstraw and Saratoga Springs, N.Y.