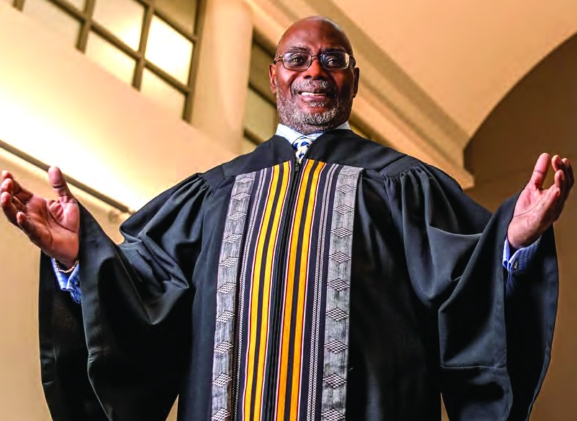

Judge Leslie Harris left an enduring mark on the legal and local community.

Judge Leslie Harris served on the bench of the Suffolk Juvenile Court from 1994 to 2014.

He has told you, O mortal, what is good; and what does the Lord require of you but to do justice and to love kindness, and to walk humbly with your God?

Micah 6:8 NRSV Three ministers and a judge arrived at this Scripture independently, believing it best summed up the life and work of Judge Leslie E. Harris. They offered separate remarks on that topic during his memorial service on Oct. 29 at Roxbury Community College.

Judge Harris transitioned to his heavenly reward from his Roxbury home on Oct. 15. He was 77.

The theme throughout the tributes paid to him was that he did indeed humbly deliver kind, compassionate justice for 20 years in Boston Juvenile Court as one who clearly knew God.

I was privileged to attend the Vigil Program for Judge Harris at a full Eliot Congregational, his home church, in Roxbury on Tuesday evening Oct. 28. I was with him over the last 40 years as we worked our way through the educational and legal communities of Boston into semi-retirement.

Before attending Boston College

Law School, Judge Harris had been the Melrose METCO coordinator, a

probation officer and taught elementary and secondary school. He

personified the persistence and perseverance required in defying the

odds against a Black person in America graduating from law school,

passing the bar, practicing law and then successfully navigating the

Massachusetts Judicial Nominating Commission application process in

order to be appointed to a judgeship.

My

most important tie to Judge Harris is the one that binds many Black

lawyers and judges in Massachusetts: The Roxbury Defenders Committee. It

speaks to who we are. Once a Roxbury Defender, always a Roxbury

Defender. I was RDC administrator from 1972 to 1974 prior to law school

and a board member after graduating.

Judge

Harris began there as a lawyer. In 1989 he represented Alan Swanson and

other defendants wrongfully arrested after the false accusations by

Charles Stuart that a black man had shot and killed his pregnant wife in

Mission Hill, following a prenatal visit to Brigham and Women’s

Hospital.

Roxbury

Defenders existed in 1989 as it does today as part of the Committee for

Public Counsel Services. However, when it began in 1971 it was

independent, having been formed by a board of community activists that

included Percy Wilson, Chuck Turner, Lenny Durant Sr. and Fredia Garcia.

They were concerned that the then Massachusetts Defenders Committee was

not adequately representing people of color in the Roxbury District

Court.

After being a Roxbury Defender, attorney Harris went to the Juvenile Division of the Suffolk District Attorney’s Office.

As some of us were taught, he practiced the prosecutorial discretion

philosophy that it was one’s duty to show mercy and keep young people

out of the system. He was stern but respectful.

That

was the philosophy he brought to the Juvenile Court bench in 1994. I

was in private practice and teaching juvenile law at Massachusetts

School of Law in Andover at that time. He encouraged me to begin

practicing in Boston Juvenile Court.

I became a member of the Children and Family Law Trial Panel.

We were charged with the responsibility of representing families in termination of parental rights cases.

Thanks

to Judge Harris, for most of his 20 years on the bench I was able to

counsel hundreds of clients appearing before him and the other justices

of his and the Probate Court as we helped people through the most

difficult situations imaginable.

Judge

Harris was always helping people, according to family and friends who

spoke at Eliot Church of the community where they all grew up, in and

around Chicago’s Ida B. Wells housing development. He moved to Boston 55

years ago, after graduating from Northwestern University, to obtain a

master’s degree in African American Studies from Boston University. One

woman described the night he raced into a burning building in their

Chicago neighborhood to save several people.

Boston

attorney Anthony Ellison, a mentee of Judge Harris as well as a former

law student of mine, and brother of Minnesota Attorney General Keith

Ellison, related the many times he appeared before Judge Harris

representing juvenile offenders. He remembered him as holding youth

accountable but at the same time leaving them with a sense of respect.

Judge

Harris was also fondly remembered for helping to found the Boston

College Law School Black Alumni Network. He is credited with mentoring

four generations of law students. He and his wife, Beverly, welcomed

hundreds of law students into their home over the years.

The ministers at the RCC service eulogized Judge

Harris for his godly compassion from the bench. His fellow Black judges,

Roderick Ireland and Milton Wright, both former Roxbury Defenders, also

spoke and knew him best.

Ireland

was the first deputy director of the Defenders and attorney Wallace

“Wally” Sherwood was the director when they were founded in 1970. They

hired me. Ireland became a juvenile judge, rising to the top and

retiring in 2014 as the first Black chief justice of the Massachusetts

Supreme Judicial Court.

Sherwood

went on to become a distinguished professor of criminal justice at

Northeastern. He left this life in 2016 after a courageous battle with

Parkinson’s disease.

At

RCC, Ireland reminded those assembled that he was a fellow congregant

of Harris at Eliot Church and praised him as a “proverbial giant.” He

said he last saw him at a Roxbury Defenders event a few days before his

death. Ireland marveled at Judge Harris’ impact on Juvenile Court legal

and social issues. He quoted the above Scripture from Micah during his

remarks.

Judge Wright,

also a member of Eliot Church, sang “Old Man River” at the service, as

he told me Judge Harris had requested. Wright also continues this year

to direct and sing in Boston’s “Black Nativity.”

At

RCC, Wright recounted being the supervising attorney at Roxbury

Defenders Committee for 13 years, including a time when Judge Harris was

a staff attorney. He recalled Judge Harris sometime afterwards

referring to him as “My boss,” to which he replied, “I was never your

boss, Leslie, because you always did what you wanted.”

Wright

provided the most humorous story of the memorial events. He told of The

Defenders successfully representing a skinhead who was so grateful he

said he was going to try to grow an afro.

Wright

and Ireland did not wear their judicial robes during the nearly

three-and-a-half-hour RCC service, but approximately 40 of their sitting

or retired judicial colleagues did. They formed a solemn column as they

followed the casket of Judge Harris from the RCC Media Center.

The

robed judges were visibly moved. Some of them had worked in Boston

Juvenile Court with Judge Harris as clerks or lawyers, including current

judges Janine Rivers, Peter Coyne, Helen Brown Bryant, Thomasina

Johnson and David Griffin. His fellow Boston Juvenile Court judge, the

retired Terry Craven was also present, along with Boston College Law

alumnus retired Housing Court Judge Wilbur Edwards.

They

were led out by the daughter of former US Attorney for Massachusetts

Wayne Budd, Kimberly Budd, the first Black female chief justice of the

Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court.

All in all, a dignified and fitting tribute to a beloved Black Massachusetts jurist.