(Top) “Untitled no. 56, Whitney Plantation, Edgard, LA” 2022; (above) “Untitled no. 17, Pacific Mills, Lawrence, MA” 2022 On the edge of te Mississippi River in White Castle, La., once stood the largest remaining antebellum plantation mansion in the United States. At 53,000 square feet, the Italianate and Greek Revival main house at Nottoway Plantation burned to the ground on May 15. Three years ago, photographer C. Rose Smith found themselves making images in and around the property, two of which are on display at Brandeis University’s Kniznick Gallery in Waltham.

Smith’s solo exhibition “A Silent Rage,” which is on display now until Jan. 8, consists of 12 black and white photographs made between 2022-2025 from plantations in Louisiana and Tennessee and a former cotton mill in Lawrence, Mass. The exhibition is part of Smith’s larger ongoing series, “Scenes of Self: Redressing Patriarchy,” which addresses the politics of dress and representation, colonial history and identity. It’s also inspired by the 1917 Silent Protest Parade in New York City organized by the NAACP.

The black and white walls in the gallery showcase photographs that place the artist in positions of prominence. Some are external shots with Smith front and center in a crisp, white cotton button-down shirt with a ramrod and dignified posture. Others depict Smith inside antebellum plantations sitting or standing in rooms where their ancestors would never be able to find rest, comfort or the freedom to create. These photographs are reminiscent of photographer Carrie Mae Weems’ “A Single Waltz in Time” from her series “The Louisiana Project,” also taken in a Nottoway Plantation ballroom.

Smith is surrounded by opulence and markers of white heritage like chandeliers, gilded frames, ancient oaks and botanical wallpaper. The settings in these photographs are made possible by the torture, trauma and forced labor of enslaved people.

In their artist statement Smith writes, “By inserting my Black, queer body into these frames, I challenge Eurocentric beauty standards and disrupt the sanitized narratives of plantation life.”

Nottoway once housed 155 enslaved people after it was completed in 1859, but the Nottaway website makes no mention of this. The only history noted on the site is the 16 ancient oak trees on the property. Eleven of those oaks are named after the children of the original owner, John Hampden Randolph. As far as Nottoway is concerned it is a successful rebrand as a hotel, wedding and event space with frequent tours of the property. Not a single mention of the devastating fire or brutal past is posted on the site.

The sweeping erasure of African American history and the sanitization of hard truths of these United States is occurring on a massive scale. The Trump administration’s efforts to restore “truth and sanity to American history” made whitewashing American history lawful with the single mark of a pen.

The administration’s efforts have been wide reaching, even directing the National Park Service to remove materials and books in gift shops that pertain to slavery. While Nottoway isn’t a federal site (it is privately owned), it is in lockstep with the current administration to romanticize the history of the antebellum South.

The Whitney Plantation in Wallace, La., is one plantation that highlights the history and legacy of slavery on their land. Dubbed by National Geographic as “the plantation every American should visit,” the focus here is on the complex and uncomfortable history that surrounds the property. Educational tours tailored to middle and high school students happen frequently. The gift shop has books about slavery, but it also has titles like “Black Boy Joy” and “Vegan Soul Kitchen” cookbooks.

It is also here at the Whitney Plantation where Smith’s “Untitled no. 56, Whitney Plantation, Edgard, LA” was made. It’s a self-portrait of them looking down into the camera’s lens in a position of power and dominance. They’re fixing their shirt cuffs while standing behind open window shutters. This reimagining of a Black body in this space highlights the central cash crop in the antebellum South — cotton.

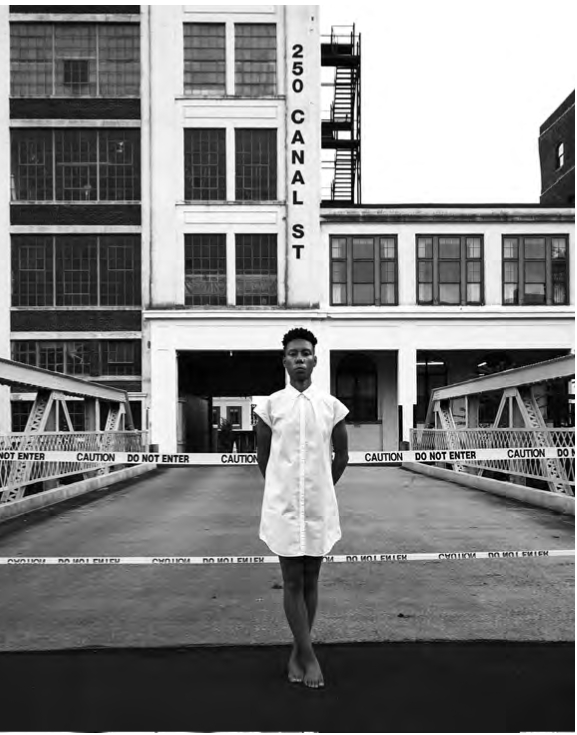

Locally, Smith’s photograph “Untitled no. 17, Pacific Mills, Lawrence, MA” was created at a former cotton mill 40 minutes north of Boston. Now an apartment building, the former mill was founded in 1852 and expanded to South Carolina on the exploited labor of “mill girls” and children. Women worked incredibly long hours and in dangerous conditions, sometimes dying on the job, with diminished pay to make a living. Even a thousand miles away from plantations, the cotton industry continued to profit from the trauma of vulnerable women, children, immigrants and enslaved people. In the image, Smith stands in front of the building, engaging directly with the viewer.

Smith’s presence in these haunting spaces is an act of reclamation.

ON THE WEB

Learn more at brandeis.edu/wsrc/kniznick-gallery