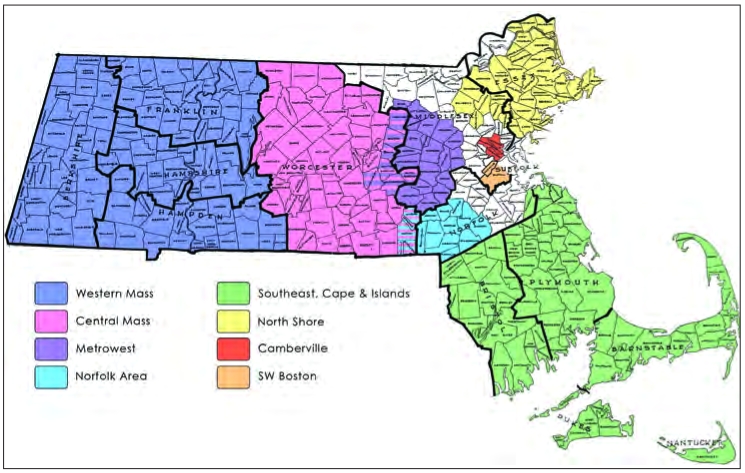

Map of Massachusetts counties

P. Brent Trottier Middle School, Southborough, Massachusetts.

DESE labels confuse rather than clarify

Massachusetts ranks each public school and district. Our accountability system designates them as “school of recognition” or “meeting or exceeding targets” at the top, opposite “focused/targeted support” and “broad/comprehensive support.” The last carries the dreaded “chronically underperforming” tag.

The labels result from an equation measuring multiple categories. Weightings vary, scoring high school completion and English language proficiency if relevant. The calculation is run twice, once for all students and again for the lowest performers. Two years of data count.

The equation generates a score from zero to one, called the criterion-referenced target. Anything over 0.75 goes in the top category, while below 0.25 means potential intervention.

The largest factor, MCAS test scores, makes all the difference. Titled Academic Achievement, this category is weighted three times more than the indicator of student growth. Top marks on test scores in ELA, math and science can contribute 0.5 towards the final result.

For most, the test score category demands large annual improvements in

student outcomes. The Department of Elementary and Secondary Education

issues achievement targets annually.

However,

plain language can be deceptive. Points for “exceeded target” and “met

target” don’t always mean DESE’s targets were exceeded or met, even

allowing for a half-point of leeway. In some cases, those points are

awarded even if test scores declined.

Once disclosed in a state publication, the details are now buried in a packet for school leaders.

DESE

rewards those at the head of the pack, so long as they maintain their

relative lead. The beneficiaries of this alternate scoring method are

less diverse, more affluent and educate fewer English Language Learners

than the state average.

The

top tenth of average scores automatically receive four points —

“exceeded target” — and the next tenth get three points — “met target.”

District scores can drop at the top of the range while receiving the

same grade as others bringing up the average.

Last

year, 398 districts, including charter schools, received targets. Of

those, 329 got points for “exceeded target” or “met target” on at least

one key test subject, but 80 of those didn’t literally meet or exceed

that subject’s target.

Test scores actually declined in 59 such districts.

Declines

of half a point or more count for 0 in the test subject. Of the

districts where scores declined while receiving three or four points

from DESE, 49 would have otherwise gotten zero.

For

example, see Southborough’s accountability data. The district’s

classification is DESE’s best. Southborough received four points for

each test subject because its MCAS scores are among the highest in the

state. Those scores dropped across the board last year.

Southborough’s

student population is 1.3% Black and 5.8% Hispanic. Massachusetts’s is

9.6% Black and 25.1% Hispanic. Southborough’s 7% ELL population is just

over half the proportion of the state’s. Likewise, the district’s 8.9%

low-income enrollment trails the Bay State’s 42.2%.

Or, consider Sherborn.

The

district is 75.6% white while the state’s public school population is

only 53%. Sherborn’s students are 5.2% low-income. Sherborn’s

achievement percentile earned the district three points in each test

category for all students. Even so, the district’s criterion-referenced

target — the equation’s output — dropped from 0.9 in 2023 to 0.62 in

2024.

Demographics are correlated with test scores.

Research

published in AERA Open measures a “moderate negative correlation”

between test-based achievement and historically marginalized student

subgroups.

On the

flipside, see the data for Dracut, Fairhaven, Revere or Worcester. Their

results were mixed and their accountability system classifications were

middling. But, where they scored three or four for academic

achievement, it was done the hard way — with a year-over-year increase

of test scores that beat expectations. Their demographics more closely

approximate Massachusetts.

The

nuances of DESE’s formula are intended to account for a variety of

academic circumstances. The guidance for setting targets once read, but

no longer does, “the criterion-referenced component of the

accountability system is compensatory,” awarding “partial credit for

improvements” through the formula “even if targets are not met.”

“The

criteria for awarding points,” it continues, “takes into consideration

districts, schools and groups that are already high-performing on this

measure by including multiple ways for full credit (three or four

points) to be earned.”

Some

high-scoring districts experienced more or less meaningless declines in

test scores year over year. Others saw substantial drops while

preserving a prestigious accountability designation.

The

Public Schools of Brookline were given a target of 525.2 for high

school ELA. Scores dropped 2.4 points to 520.2 in that subject, but

Brookline still got four points for “exceeded target.” Approximately the

same story played out in Winchester.

In

Wellesley, high school math scores declined by 4.6 points, when the

target called for a 2.5-point increase. The district, DESE said,

“exceeded target.”

Hingham’s

high schoolers were asked to get a 520.8 on science. Instead, they

dropped 6.5 points and the district got “met target.”

With

two exceptions, the 80 districts that were boosted by the percentile

scoring criteria populate the top two categories of DESE’s

accountability system. Last year, 44 districts scored in the top tier,

“meeting or exceeding targets” and 38 benefited from the relative

scoring method.