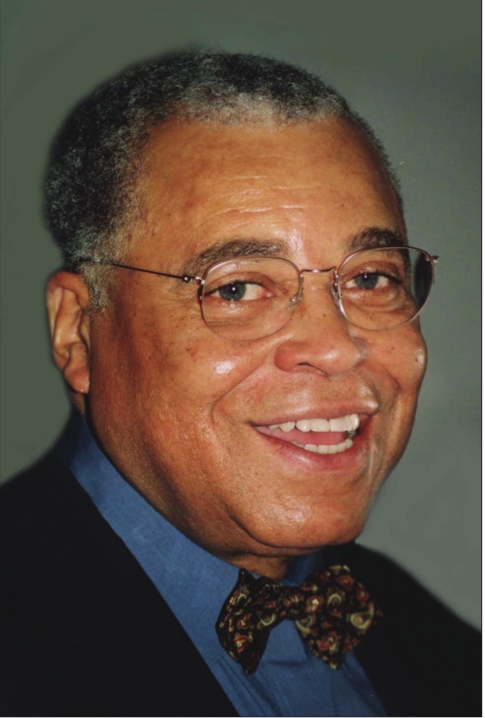

James Earl Jones

James Earl Jones

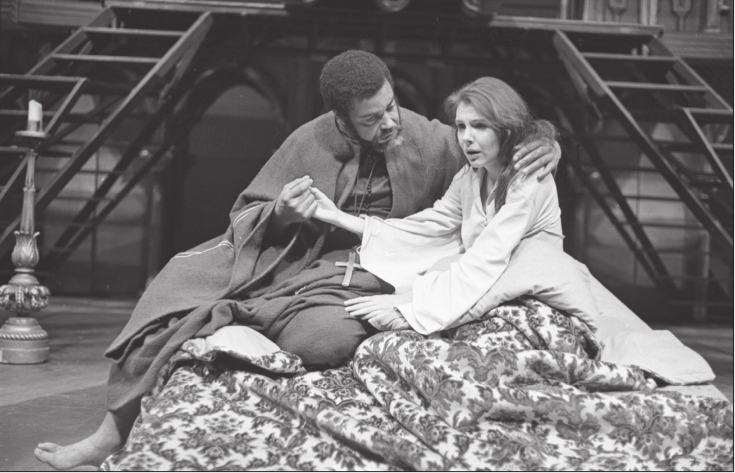

Actors James Earl Jones and Jill Clayburgh in a Los Angeles stage production of “Othello,” in 1971.

When James Earl Jones passed away on Sept. 8 at the age of 93, stories and accolades poured in from everywhere. I started thinking about the impact Jones has had on the entertainment industry and the world in general. It dawned on me that there is probably no place in the world that does not hear his voice 24/7, 365 days of the year, because he’s the voice of CNN.

“I just emptied my mind, then filled it with the thought of all the hundreds of stories — tragic, violent, funny, touching — that could be following my introduction,” he said when asked about his motivation for that voiceover. “And then I said, ‘This is CNN.’”

Yes, it is that voice that tamed Lion Kings and put the fear of Darth Vader into every corner of the planet.

Jones, who burst into national prominence in 1970 with his powerful Oscar-nominated performance as America’s first Black heavyweight champion in “The Great White Hope,” died at his home in Dutchess County, New York, Independent Artist Group announced. He had a 70-plus year career and had to overcome a disability of stuttering, which apparently was from childhood trauma after his parents abandoned him and left him to be raised by his grandmother, whom Jones claimed was extremely racist.

“I was raised by a very racist grandmother, who was part Cherokee, part Choctaw and Black,” Mr. Jones told the BBC in a 2011 interview. “She was the most racist person, bigoted person I have ever known.” She blamed all white people for slavery, and Native American and Black people “for allowing it to happen,” he said, and her ranting compounded his emotional turmoil. Traumatized, James began to stammer. By age 8, he was stuttering so badly that he stopped talking altogether, terrified that only gibberish would come out. He communicated by writing notes. Lonely, self-conscious and depressed, he endured years of silence and isolation. When an English teacher in high school encouraged Jones to read a poem to the class that he had written, he discovered that his stutter vanished whenever he spoke words that he had memorized. He won a public-speaking contest as a senior and earned a full scholarship to the University of Michigan, where he studied medicine and discovered acting. He made his stage debut in a community theater production in Manistee, Michigan, before he left to serve in the Korean War.

In the 1970s and most of the ’80s, Jones was in constant demand for stage work in New York, films in Hollywood and television roles on both coasts. His prodigious body of work encompassed scores of plays, nearly 90 television network dramas and episodic series, and some 120 movies. They included his voice work, much of it uncredited, in the original “Star Wars” trilogy; in the credited voice-over of Mufasa in “The Lion King,” Disney’s 1994 animated musical film; and in his reprise of the role in Jon Favreau’s computer-animated remake in 2019. Mr. Jones was a rock. He once appeared in 18 plays in 30 months. He often made a half-dozen films a year, in addition to his television work. And he did it for a more than half-century, giving thousands of performances that captivated audiences, moviegoers and critics.

Jones was one of the first Black actors to appear regularly on the daytime soaps, playing a doctor in “The Guiding Light” and in “As the World Turns” in the 1960s. Television became a staple of his career. He appeared in the dramatic series “The Defenders,” “Dr. Kildare,” “Touched by an Angel” and “Homicide: Life on the Street,” and in mini-series including “Roots: The Next Generation” (1979), playing the author Alex Haley. Onscreen, Jones also was memorable as “Few Clothes” Johnson in John Sayles’ “Matewan” (1987), as Rev. Stephen Kumalo in the apartheid drama “Cry, the Beloved Country” (1995) and as Robert Duvall’s embittered half-brother in “A Family Thing” (1996). He played Admiral Greer in three films based on Tom Clancy novels: “The Hunt for Red October” (1990), “Patriot Games” (1992) and “Clear and Present Danger”(1994), and was King Jaffe Joffer in the pair of “Coming 2 America” movies, including the 2021 sequel. Jones’ two Emmys came in 1991 for playing a private detective who was wrongly imprisoned on the short-lived ABC drama “Gabriel’s Fire,” and as the owner of a shoe-repair business in the TNT telefilm “Heat Wave,” about the 1965 Los Angeles Watts riots. Among the myriad roles he played onstage were Thurgood Marshall, the first Black justice of the U.S. Supreme Court, Big Daddy in “Cat on a Hot Tin Roof,” President Arthur Hockstader in a revival of “The Best Man,” and chauffeur Hoke Colburn in “Driving Miss Daisy,” opposite Angela Lansbury.

Jones took occasional breaks at a desert retreat near Los Angeles and at his home in Pawling, New York. He joined Joseph Papp’s New York Shakespeare Festival in 1960; over several years he appeared in “Henry V,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Richard III” and “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

During a long run as Othello in 1964, he fell in love with Julienne Marie, his Desdemona. They married in 1968 but divorced in 1972. In 1982, he married the actress Cecilia Hart, who had also played Desdemona to one of his Othellos. She died in 2016. Their son, Flynn Earl Jones, survives him, along with a brother, Matthew.

The distinguished star is the recipient of an honorary Oscar at the 2011 Governors Awards and a special Tony for lifetime achievement in 2017. He was one of the handful of people to earn an Emmy, Grammy, Oscar and Tony, and the first actor to win two Emmys in one year.

I first met James Earl Jones when I was doing my show, “Coming Together” in Boston. We talked a lot about his early beginnings, mainly because he grew up in Western Michigan, not far from where I was born. I do remember him sharing his challenges of overcoming stuttering. He said he would often put small stones in his mouth when he was learning to speak and it really worked for him. In 2022, the 110-year-old Cort Theatre on Broadway was renamed The James Earl Jones Theatre in his honor.