A

car charges at an electric vehicle charging station in a municipal lot

off Mattapan Square. State leaders are looking to promote electric

vehicle uptake with increased charging infrastructure and better

education about the vehicles.

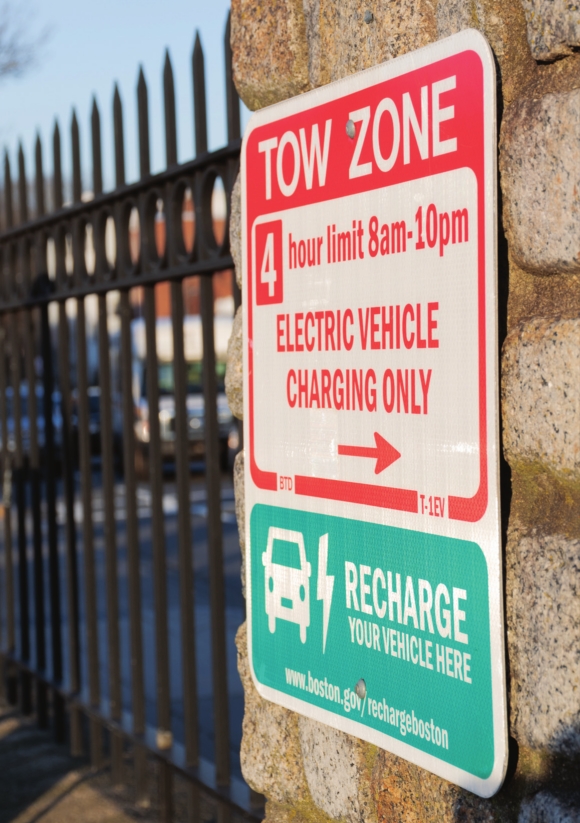

A sign marks an electric

vehicle charging station at a municipal lot off Mattapan Square. State

leaders are looking to promote electric vehicle uptake with increased

charging infrastructure and better education about the vehicles.When it comes to reducing carbon emissions, electrifying the vehicles Massachusetts drivers use is a prime target for those reductions.

According to state data, in 2020, transportation accounted for about 37% of carbon emissions in the state, the most of any sector.

But even as the city and state grapple with connecting more drivers to electric vehicles, barriers still exist. High costs, especially for new vehicles, can cast electric vehicles as a luxury purchase. Limited charging infrastructure can limit access for residents, especially those without their own garage or driveway to charge in. And concerns around the range of the vehicles persists.

Top of mind for people working in the electric vehicle space in Massachusetts is connecting people in apartments and other multifamily housing without a place at home to park a car — socalled “garage orphans” — with access to charging.

“Thinking about how we can address renters and garage orphans is really a sticky barrier that we’re grappling with,” said Assistant Secretary of Energy Josh Ryor.

Increasing access to public chargers could help reduce the concerns of prospective drivers, said Justin Ren, a professor of operations and technology management at Boston University.

“If I can’t charge a car, there’s no use, right? So that’s one major hurdle. Can we do better in terms of providing public charter infrastructure?” said Ren, who is a core faculty member at the Boston University Institute for Global Sustainability.

It’s a topic that’s in focus. At the Sept. 4 meeting of the

state’s Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Coordinating Council, three

different companies, each focusing on increasing on-street charging

infrastructure, presented to the council on their work.

That

included companies that are part of an effort in the city of Boston to

increase curbside charging, part of a goal to bring charging

infrastructure within a five-minute walk of every resident in the city.

Boots-on-the-ground

efforts of installing the infrastructure, like in Boston, will largely

be up to municipalities, Ryor said, but the state is looking to provide

assistance to cities and towns in the state, including by directing

$11.25 million in funding to the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center to

create a program supporting municipal efforts to expand on-street

charging.

The request

for proposals for that Massachusetts Clean Energy Center on-street

charging program closed Sept. 4, and a representative for the center

said they hope to notify awardees by October.

But

convincing some drivers that nearby on-street charging is a viable

option would still remain a hurdle. A new study from Boston University’s

Institute for Global Sustainability and the National Renewable Energy

Laboratory that looked at barriers around electric vehicle uptake found

that just over half of individuals who

responded to their survey said they would never be willing to park

their EV away from their home to charge it. Another 21% said they’d be

willing to walk about a quarter of a mile — about the distance, on

average, covered Boston’s five-minute walk goal.

Charging infrastructure along highways, as well as the limited driving range of electric vehicles, continues to present a

concern for some drivers. The research from Boston University found that

16% of its survey respondents identified a more limited driving range

as a high barrier to electric vehicles.

Battery

electric vehicles tend be capable of driving between 100 and 400 miles

on a full charge, versus the general range of 250 to 700 miles of

combustion engine vehicles.

“If

I want to make a trip to New Hampshire, it’s going to take 300 miles,

more or less, and I just don’t want to be stranded,” said Ren, who was

not involved in the study. “Those are the kinds of concerns that are

keeping at least some people away from buying a buying electric car.”

Some

of that range anxiety is a matter of perception. Ryor pointed to

federal alternative fuels data from the Department of Energy in

comparison to the state’s Clean Energy and Climate plans and said that

he thinks the state is on track for deploying fast chargers that can get

drivers back on the road more quickly.

The

state’s Department of Transportation is looking to increase awareness

of those stations by expanding signage identifying charging stations

along state highways. At the Sept. 4 meeting of the Electric Vehicle

Infrastructure Coordinating Council, Chris Aiello, senior council for

the Department of Transportation’s Climate Initiative, said the

department had implemented a new policy around signage advertising EV

charging allowing for the signs on state highways.

“Range

anxiety remains a key barrier to EV adoption. The hope is these signs

will provide helpful information to EV drivers, but the signs will also

help to make non-EV drivers … aware of the growing network of fast

chargers along the state highways,” Aiello said at the meeting.

The

charging stations, if advertised, must be available to the public

around the clock and located within three miles of the exit. Under the

policy they will appear on roadside signs in the same way that gas

stations, food and lodging can be advertised along highways.

But

some of that charging landscape still needs to be built up. In

December, the state announced a plan to establish a network of fast

chargers in the state, looking to tap pre-qualified vendors to design,

permit and build chargers at locations along state roadways.

In

a press release at the time of the announcement, transportation

Secretary Monica Tibbits-Nutt said she thinks an expanded network will

attract more drivers to electric vehicles.

“Fast-charging stations at convenient locations along major roads will absolutely lead to

reduced air pollution, fewer gas-guzzling cars on our roads, and a

willingness by people to make smarter choices which will help combat

climate change,” she said.

The

reputation of electric vehicles of being a big-ticket purchase also can

dissuade drivers. According to Kelley Blue Book, as of January, the

average new electric car, before any state or federal rebates, cost over

$50,000, about 4% more than the overall new car market.

Some of that has changed.

Ren

pointed to five years ago, when most people would have looked only to

Tesla and its price tag that could reach up to or past $50,000 as their

reference for personal electric vehicles. For example, around the end of

April, 2021, Tesla sales made up about two-thirds of electric vehicle

scales, also according to Kelley Blue Book.

That’s

changing, though Telsa still is dominant. As of June, Tesla sales made

up just over half of all new electric vehicle sales in the United

States.

And the state is looking to make electric vehicles more affordable by expanding rebates.

It’s

MOR-EV — Massachusetts Offers Rebates for Electric Vehicles — program,

was expanded last year, with a new program for used electric vehicles

and additional incentives for lower-income residents and for swapping in

a combustion engine vehicle.

But

attracting drivers to some of those opportunities, like purchasing used

vehicles may require some work. The Boston University study found that

among all income brackets surveyed, drivers were more likely to look for

an electric vehicle new rather than used. Even among respondents making

$15,000 or less per year, if they were to consider buying a electric

vehicle, the likelihood of them buying a used electric vehicle was over

20 percentage points lower than if they were looking to buy a car

generally.

Ryor said that he hopes increased education around electric vehicle incentives might increase uptake of things like used EVs.

A

state equity report, released by the Healey-Driscoll administration at

the end of August identified improving outreach — especially in multiple

languages — and increasing education around the program as areas where

the state’s rebate program could grow stronger.

The

new Boston University research suggested that to get more drivers

behind the wheels of electric vehicles — especially in a way that

doesn’t leave communities behind — more focus needs to be given to the

human side, rather than the engineering.

“Equitable

deployment of PEVs and charging infrastructure may require a shift in

focus from a technology and innovation focus on “vehicles” to a more

holistic approach to the “people” who own and drive them,” the authors

wrote.

It’s a sentiment that Ryor said the state shares.

“We have to make sure when we’re designing these

programs and thinking through how to address these problems that we’re

meeting people where they’re at,” he said.

He

said that means engaging with the Office of Environmental Justice

within the Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs, as well

as a specific push for “culturally competent” outreach tailored toward

underserved communities, communities with a high percentage of

low-income households and those with a high proportion of high-emissions

vehicles.

That

type of outreach, focused on and for specific communities, is an

important step to bring more people into the fold, Ren said.

“We

need to understand what’s the context,” he said. “We need to design the

education programming to speak to a particular culture.”

Improving

education in diverse communities was one area for growth identified by

the state equity report, which suggested that kind of education could

“meaningfully expand the conversation around who thinks they belong in

an EV.”

And a

state-funded effort through the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center would

aim to bring more educational resources about the state’s rebate program

to residents in the state, including information translated into other

languages like Spanish, Portuguese and Haitian Creole.

Ryor

said outreach to environmental justice communities needs to be specific

to each one of those communities — and that, despite all tending to

bear the brunt of environmental impacts shouldn’t be treated as monolith

— but said that those communities will be key to making a transition to

electrified travel.

“Frankly,

it’s not possible for us to meet our climate goals without making sure

that we’re including environmental justice communities and that these

folks are able to access electric vehicles and make that transition as

well,” Ryor said.