“Dance Slam” ran for 10 weeks in summer 1989.

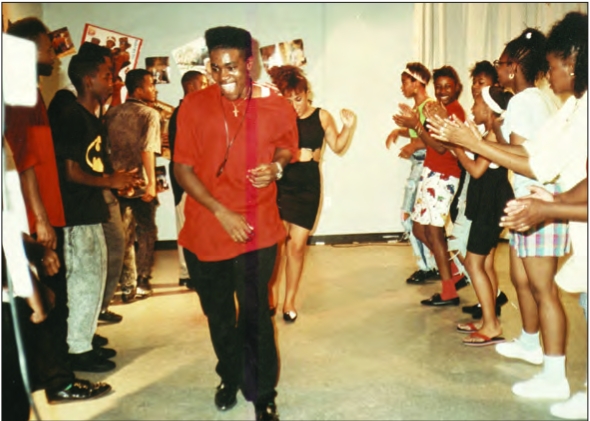

Teens dance on the set of “Dance Slam,” the live music and dance show that aired in the summer of 1989.

35 years ago, a TV program let Black teens boogie the summer away

Dashes of static flash across the bottom of a black screen. An upbeat song begins and an enthusiastic voiceover booms. “Live from Roxbury, Massachusetts…” the announcer’s voice echoes. The black screen disappears, and in its place, the camera pans across a room full of teens dancing to the beat.

With their baggy tees, flat top haircuts and headbands — all typical of ’80s and ’90s couture — the group of dozens of teens

boogie in front of a wall covered in posters. “...It’s ‘Dance Slam’!”

the voiceover continues. A record-scratch-like sound effect plays, and

the first verse of the bouncy hit “Rollin’ With Kid ‘N Play” comes on.

It

was 1989 in Boston, and out on the streets, fatal crimes and gang

violence were pervasive. Many of the victims were kids in Roxbury and

Dorchester. “Dance Slam,” a weekly music and dance program that aired 35

years ago, was created to give Black teens a reprieve from the chaos

outside, and the man behind it knew intimately what it was like to need

one.

Tony

Rose grew up in the Whittier Street housing projects, a multi-story

complex in Lower Roxbury between Tremont, Ruggles, William and Cabot

Streets.

His family

was poor, much like most of the approximately 5,000 people who lived in

the buildings, many of whom relied on public assistance.

“It

was not a happy time,” recalled Rose, 70, who now lives in Phoenix,

Arizona and runs a publishing company with his wife, Yvonne Rose. “You

had to make your happiness.”

He

began his pursuit early by taking up entrepreneurship. At the age of 6,

he learned how to sell newspapers, first making fivecent gains by

vending the Record American. After mastering the art of buying low and

selling high, he added the likes of the Boston Sunday Globe and the

Christian Science Monitor to his rotation, until he had about five

newspapers in his inventory.

Pennies

and nickels turned into whole-dollar profits, and the young maven

supplemented his income by picking up other odd jobs such as running

numbers and shining shoes.

Newspapers and errands made him money, but by 11, Rose had discovered that music was his passion.

His

grandmother, a New Orleans woman from a line of French-speaking African

Americans, had gifted Rose a transistor radio. He would place the

device under his pillow, falling asleep to the music and hearing the top

hits all through the night, he recalled. Through this habit, he began

to understand “the nuances of music,” he said. He quickly learned what

comprised a good song, and knew he wanted to produce some.

Rose,

a U.S. Air Force veteran of the Vietnam War, left Boston at 22 and

landed a job as a production assistant in Los Angeles, along with other

positions at various record companies. This was the start of a strong

career in music that included working with Maurice Starr, starting his

own record company and winning awards for recording and engineering.

In

1989, after having returned to Boston and being one of the architects

of the city’s Black music scene, Rose saw an opportunity to use music to

change his hometown and neighborhood. He had grown up in poverty, in an

environment where male role models were scant — his own father had been

in jail — and he wanted to offer the Black teens of Boston an

alternative.

“One of

the things that he really wanted to do was find a way to give back to

the community…He wanted to have a vehicle for the teenagers,” said

Yvonne Rose.

Inspired by his time on the West Coast, Rose thought to emulate “Soul Train, the music variety show that began in 1970s Chicago.

“I

thought that idea I had might be able to get some kids off the street,

into music more, and come to the studio and hang out and be recorded,

see what they could do with their lives,” Rose said.

Rose

had his finger on the pulse. He was a music producer, had his own

studio and had a band. He channeled his experience into ideating a new

music show and drafted a proposal for “Dance Slam,” which he said would

be “Boston’s first Black dance-music-video television show” and would

attract 50,000 weekly viewers. He shared the proposal with Dan

Richardson of Boston Neighborhood Network, or BNN, who became “Dance Slam’s” producer alongside Rose.

Rose tapped Mike Shannon of WILD as the show’s host and his wife as one of the co-producers.

With

the show’s concept finalized, Rose began publicizing the program. He

advertised heavily on WILD, the radio station dedicated to R&B, and

created promotional materials. One flyer invited “beautiful boys and

girls between the ages of 15 and 21 years old for a new music television

video-dance show.”

The

poster labeled the show “the first of its kind in Boston and guaranteed

to be rockin’!!!” and provided a phone number. On the bottom, the flyer

included a call for local bands, singers and rappers who were

interested in participating.

With

a decade of experience in the industry, Rose was well-connected, and

his clout came in handy. Record companies in New York with whom he’d

been doing business sent him the

latest music videos and records they could play on the show. He also

secured sponsors like Mattapan Music, Nubian Notions and a limousine

company.

On July 8, 1989, at 11:00 in the morning, Rose’s idea came to fruition, as “Dance Slam” aired for the first time.

Recorded

live from a studio on Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard in Roxbury, the

show featured a medley of hip-hop and R&B music videos,

choreographed dances and singing, with host Shannon popping in

sporadically to announce the next segment or ask the teens questions.

The talk of the town

During

the summer “Dance Slam” ran, hundreds of kids from Roxbury, Dorchester,

Mattapan and Jamaica Plain “flocked to the studio” for a chance to be

broadcast, recalled Yvonne Rose.

“The

kids were excited to be there, and they were all friendly,” she said.

“Nobody caused a problem … but they were eager to learn and eager to be a

part of something that was bigger than them … It was a

community-spirited situation.”

The teens showed up for a chance to see themselves on TV while distracting them from what was happening on the streets.

For

a couple of minutes every Saturday that summer, Black teens danced

freely to the latest hits. The camera focused on the dancers with the

best moves and personalities, Yvonne Rose said.

In

the first episode, a young girl sporting an updo and a bright green and

pink top was a recurring presence on screen, thanks to her dynamic

gestures.

The

participants were proud to be on “Dance Slam,” and their parents were

proud, too, Yvonne Rose added. Soon, “Dance Slam” became the talk of the

town, “because it was one of the most exciting things that was going on

at that time,” she said.

Dancing

was the main attraction, but the show also included educational

segments, some about health, and featured local DJs, including “Pebbles”

from WILD.

In trying

to get “Dance Slam” off the ground, Rose hit some snags along the way,

including struggling to secure the ideal time slot for the program, but

in the end, the 10-episode show achieved what he hoped it would.

“It

was awesome, just awesome,” he said. “It got kids to [know] one

another, whether they were from different sections of Roxbury or

Dorchester or Mattapan, they got to meet and like each other and become

friends.”

One of the

participating teens, Keisha Echola, told the Banner back in 1989 that

“watching it, watching them record it, and being on the show” was fun.

“You do a lot of dancing and sweat a lot,” she said.

The

program was well-received. Community members, local businesses and

record shops advertised on the show. Beyond the business, Rose said he

was especially proud of “the children and kids that were there to

participate in the programming, and how enthused they were to have this

in their midst.”

For them, Saturdays during the summer of 1989 were joyous.