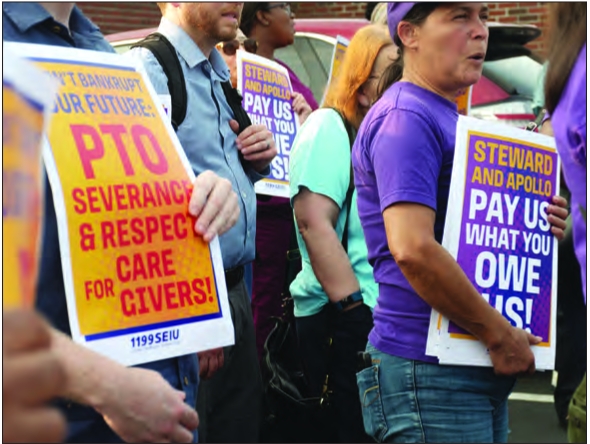

Supporters

of 1199SEIU, the union for health care workers at Steward Health Care’s

seven active Massachusetts hospitals, hold signs at a rally ahead of a

public hearing on the pending closure of Carney Hospital. 1199SEIU was

calling for Steward to pay severance and paid time off to staff at

Carney Hospital if the pending closure goes through.

Carney still set to close at the end of the month, despite pushback

Five of the seven remaining hospitals owned by Steward Health Care are on their way to officially being under new ownership, according to an announcement last week by Gov. Maura Healey.

At a press conference Friday, Aug. 16, Healey said that Good Samaritan Hospital in Brockton, Morton Hospital in Taunton, St. Anne’s Hospital in Fall River, Holy Family’s Haverhill and Methuen campuses, and St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Brighton are all in the process of being purchased and taken over by new hospital systems.

While the paperwork has to be finished, she said this step effectively removes the presence of Steward Health Care from the state. Healey’s announcement followed a hearing in the Dallas-based bankruptcy court the same day.

“It is a new chapter, starting today. A new chapter for patients and residents, a new chapter for our great health care workers — our incredible nurses, health care workers, all the staff, the people who actually make our hospitals run,” she said.

Carney Hospital in Dorchester and Nashoba Valley Hospital in Ayer, slated to close at the end of the month, will not be included in that new chapter.

For four of the hospitals — all but St. Elizabeth’s — the deal was squared away in court; while for that last hospital, the landlord has refused to move. In response, Healey announced the state’s intention to seize the hospital through eminent domain.

That move will allow for the transfer of the hospital to Boston Medical Center, who made a bid to purchase the campus.

The action follows a push for an eminent domain takeover at the two Steward hospitals that are set to close, to keep the facilities operational,

but Healey said that the situation there is different from the one at

St. Elizabeth’s, where a new operator is lined up to take over.

At

Carney and Nashoba, without any qualified bids— a designation

determined by the bankruptcy court, not the state — Healey said the

state cannot keep the hospitals open.

“The

state cannot run a hospital. Hospital systems have to run hospitals,”

she said. “The difference here is we had five hospitals where hospital

systems, as acquirers, came forward to take over operations. That,

unfortunately, did not happen with Carney or Nashoba.”

The

transfers mean that the five hospitals will transition out of the hands

of the for-profit Steward Health Care and into the hands of nonprofit

operators.

In addition

to St. Elizabeth’s Hospital, Boston Medical Center was also announced

as the soonto-be new owner of Good Samaritan. Lawrence General Hospital

will take over the two Holy Family campuses. Lifespan Health System,

based in Providence, Rhode Island, will take over operations at Morton

and St. Anne’s.

Deep concerns over Carney

But community members in and around Dorchester were not ready to let the closure of Carney Hospital go quietly.

As

the dark of night fell on Aug. 13, for three and half hours, Carney

Hospital supporters, staff and patients — who were often one and the

same — described at a state Department of Public Health hearing the way

the hospital had impacted their lives and what it would mean for the

local community if its slated closure at the end of the month goes

through.

The public

hearing, held at Florian Hall in Dorchester, was one of the latest steps

in an expedited closure process that has raised concerns from staff and

community members.

The event was well-attended by elected and appointed officials.

Beyond

the staff from the state’s Division of Health Care Facility Licensure

and Certification, who ran the hearing, city councilors and town

selectboard members from Boston and surrounding communities that

regularly rely on services at the Dorchester hospital spoke. State

senators and representatives — as well as candidates for those offices —

were in attendance.

Dr.

Bisola Ojikutu, who heads the Boston Public Health Commission, spoke on

behalf of her organization and the Wu administration as a whole. Dr.

Robbie Goldstein, the state’s public health commissioner, stayed for the

whole hearing.

The array of officials underscored concerns about the broader impact that the closure could have.

“Carney

Hospital has been a lifeline for so many, particularly to those from

underserved communities who may struggle to access health care

elsewhere,” said Erin Bradley, a member of the Milton Select Board. “The

closure of this facility will create a ripple effect, placing

additional strain on other hospitals and health care providers and

leaving many without critical care they desperately need.”

Many

hospital supporters, however, said they felt abandoned by those

officials, who largely spoke about the importance of the hospital but

had little in the way of specific solutions to keep it open.

Some

proposed solutions have been floated. Groups including the Boston City

Council have called for the city or state to pursue a public health

declaration to halt the closure.

On

Aug. 7, the City Council passed a nearly unanimous resolution — 12

voted in favor, while District 7 Councilor Tania Fernandes Anderson

voted “present,” citing a desire for more time to speak with

stakeholders — urging the city and Boston Public Health Commission to

declare a public health emergency and take all steps necessary to keep

the hospital open.

The

recommendation included going so far as to suggest that if no qualified

bidder comes forward to purchase the hospital, the city and state

should be prepared to seize the hospital by eminent domain and to run it

until a permanent operator can be found.

But

the prospect of a local declaration of a public health emergency seems

slim. At the Aug. 13 public hearing, Ojikutu said that the city doesn’t

have the licensing authority or financial resources to keep the hospital

running.

“As the

city’s local health department, we cannot stop the closure of Carney

hospital and I’m saddened to say that,” Ojikutu said. “Some have

suggested that we declare a public health emergency. Declaring a public

health emergency will not give the city, Mayor [Michelle] Wu or I the

regulatory authority, the licensure ability, or, most importantly, the

money that it will take to run Carney hospital, even in the short term.”

She

said the city would not be declaring an emergency but instead is

focused on ensuring access to care following the end of the month.

At

the hearing, District 3 City Councilor John FitzGerald said while there

might be limited options to take over the hospital but suggested that —

given the claims that the closure of the hospital is necessary given

limited market support to keep them open — there should be efforts to

make running it profitable.

“I

understand the legal side of things, that we have no levers, and

there’s only so much we can do, so people are just throwing in the towel

at the state and at the city. I get that, but we still can create the

environment for which to make this hospital profitable for whoever’s

running it, and great care for whoever needs it.”

For

him, that means taking steps like the one pursued by Wu at the start of

the month to make the possible redevelopment of the hospital into

something like new housing an uphill battle.

In

an Aug. 1 letter, Wu told the companies that own the land on which

Carney stands that she would oppose any attempt to rezone the land for

uses other than health care.

If

developers were to look to rebuild for new uses at the site, zoning

would currently allow only for residential housing with a maximum height

of the three stories.

“At the end of the day, you have to talk dollars and cents to these people,” FitzGerald said in an interview.

He

said he believes a model exists that could make continued operations of

the hospital profitable, but that the hospital and its supporters need

more time to show what that model could be. He said that means getting

the full 120-day closure period that state regulations outline — Steward

Health Care’s proposed closure plan gave only 36 days in all — but also

looking for more time beyond that to show that operations can make

financial sense.

But he said that he thinks it’s important that steps can be taken before the closure happens.

“Once it shuts down and the nurses get new jobs and the surgeons go elsewhere, what are you opening back up?” FitzGerald said.

How to get that extra time remains a question, though.

Limited options

In

a statement to the Banner, a spokesperson for the Department of Public

Health said the state is pushing Steward to observe the 120-day closure

period, but said that the leverage that would normally exist — revoking a

hospital’s license — is not effective here, as Steward is already

willing to give that up.

An emergency declaration seems similarly unlikely at the state level.

In

an interview on WBUR’s Radio Boston on Aug. 12, Healey acknowledged

that a public health declaration could be an option to keep Carney

hospital open, but said that it doesn’t consider questions around how

those hospitals will continue to be funded, continuing her ongoing

position that there isn’t anything she can do.

At the press conference last Friday, she said without a new bid coming in, she considers the state out of options.

“If [a bid] were to miraculously appear, that would be another thing, but where we are today, this is all we can do,” she said.

In

the meantime, the state has put up $30 million to keep Carney Hospital

and Nashoba Valley Hospital open through the end of the month, when

Steward said it intends to close both facilities.

Supporters, staff push back

Supporters

at the hearing were frustrated at claims that there is no money to save

Carney Hospital, pointing to recent large state expenditures like the

$93.5 million the state directed toward making community college free

across the state or the $8.83 billion so-called “rainy day” or

Commonwealth Stabilization fund.

The

concept of contingency planning for what should happen if the hospital

does close on Aug. 31, the date on which the pending closure is slated,

was a touchy subject at the hearing.

Department

of Public Health officials pointed to ongoing planning to adjust and

adapt if Carney Hospital does close. In May, the Healey-Driscoll

Administration activated an Incident Command System in response to the

financial challenges faced by Steward Health Care and the possibility of

closures.

But supporters of the hospital largely opted to reject discussions of what to do if the hospital does close.

“The

only viable contingency plan to protect the community at Carney

Hospital is to not close Carney Hospital,” said Katie Murphy, president

of the Massachusetts Nurses Association.

However,

the question was a necessary one for Carney staff with 1199SEIU, the

health care workers union. Staring down the pending closure, they are

facing — and pushing back on — concerns that with the rapid and abrupt

process, Steward might not honor the severance pay and paid time off in

their contracts.

At a

rally ahead of the public hearing, Karl Odom, an 1199SEIU delegate at

Carney Hospital, said that for years, in negotiating with Steward Health

Care, requests for more time off were met with reminders that even an

extra day came with a cost, something that often meant time off wasn’t

expanded. Now, “that cost is here,” he said.

“That

is money owed, that’s money that we should be paid, and we’re not going

to give that up, no matter what,” said Odom, who has worked at the

hospital for more than 40 years. “We took care of the patients. We

stayed because we didn’t want to leave our coworkers behind. We worked

hard for them. Now it’s time.”

The

discussion is especially pertinent for staff who limited or passed on

taking time off because the facilities were short-staffed.

At

the hearing, Bruce Berman, who has worked as a psychiatric counselor at

Carney Hospital for 40 years, recalled hearing a Carney employee of

more than 30 years speak at a recent town hall about what it would mean

for her and her family to her to lose her job without receiving the 28

weeks of severance and paid time off she is due.

“Imagine

giving your life and your heart and your soul to a place for over three

decades, only to face the harsh reality of unemployment and the

possibility of not being compensated for the time and effort you’ve

invested,” he said. “We are not just talking about numbers on a piece of

paper. … The severance and PTO that was agreed upon in our contract is

not just a benefit, it is a promise that we now demand to be honored.”