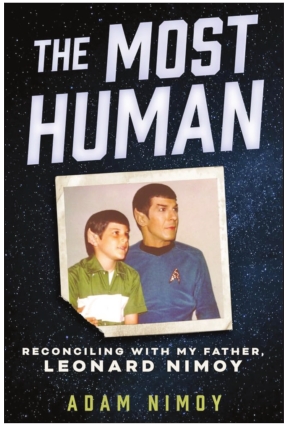

Star Trek star Leonard Nimoy talks with his son Adam at the West End Museum in 2013.

Adam Nimoy at a 2016 “Star Trek” fan event in New York.

Adam Nimoy visited the West End Museum as part of a book tour for his new memoir.

On June 30, Adam Nimoy spoke in Boston at The West End Museum as part of a book tour for his new memoir “The Most Human: Reconciling With My Father, Leonard Nimoy” (Chicago Review Press, June 4, 2024).

It was the younger Nimoy’s second visit in a decade to the museum, which opened in 2004 and has just undergone a major restoration following a January 2022 flood, caused by a burst pipe on the fourth floor of the West End Place mixed-income complex above. The Lomasney Way site keeps alive the memories of the beloved immigrant neighborhood that fell to demolition in the late 1950s in one of the city’s most notorious examples of “urban renewal.”

Nimoy’s prior stop was in 2013 during a documentary film shooting project about his father, the iconic, West End-bred “Star Trek” actor. Two years later, the elder Nimoy passed away in Los Angeles from COPD at age 83.

Like all former residents of Boston’s West End, Nimoy retained a great love for the area, and strong animosity over its fate. But long before bulldozers razed the beloved immigrant enclave, the West End, which began in the 1700s as farmland, had a history of major change for its residents — which as noted in the West End Museum’s online archives, included the Black community. In the 1700s, during the Revolutionary War, the city’s militiamen prevailed upon General Washington to recruit their Black neighbors into the Continental Army.

Flourishing Black community

Boston became known as a welcoming place for free Black Americans, and by the 1800s, the West End was a Black neighborhood called “West Boston.” The community flourished and built the oldest standing Black church in the country and a school. Its elite population included abolitionist, journalist and publisher William Cooper Nell, who led a movement for equality in schools, and Lewis Hayden, who escaped enslavement and who, according to the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, was active in Boston’s Underground Railroad network, served on the executive committee of the Boston Vigilance Committee, hosted abolitionist meetings and operated a safe house for those seeking freedom.

Unfortunately, the immigration era led to racial segregation in the city. “With the arrival of Germans and Irish in the North End in the early 1830s, Black residents there were pressured to leave,” the WEM archives continue. “The majority of Black North Enders relocated to the North Slope of the West End, significantly elevating the neighborhood’s share of Boston’s total population.” That consolidation lasted for several decades. But unfortunately, the WEM site notes, “the burgeoning forces of segregation persisted and intensified through the latter half of the 19th century and beyond, eventually forcing most Black Bostonians out of the West End.”

Nimoy spoke about his father’s own journey, and landing on the small screen in a custom-made role. “Even in 1964 when nobody had heard of ‘Star Trek,’ the 8-yearold me had watched enough sci-fi TV shows to understand exactly what I was looking at,” he told the WEM audience. “A scary but benevolent alien accidentally arrives on earth and is misunderstood and treated badly, and is someone who always appeals to us outsiders and social distancers trying to find our way. And now here was Dad playing the half-human, halfalien spot, soon to take that to a whole new level.” As he would later tell, that role was emblematic of his dad’s own personal evolution, which began in Boston.

Nimoy was likely not the

only actor who found fulfillment on the show. “Star Trek” featured a

pioneering multicultural, multiracial crew that included myriad actors

of African descent in its original series, which ran from 1966-69. They

included Nichelle Nichols as Lt. Nyota Uhura; Carl Byrd as Lt. Shea;

Percy Rodrigues as Portmaster Stone; Don Marshall as astrophysicist

Boma; Lloyd Haynes as Communications Officer Alden; Phil Morris, who

played a boy in the “Miri” episode and appeared in “Star Trek III: The

Search for Spock,” “Babylon 5, Star Trek: Deep Space Nine,” and “Star

Trek: Voyager”; Vince Howard, who appeared in the first season episode

“The Man Trap” and played the M-113 creature; Iona Morris as Umali;

Booker Bradshaw as Dr. M’Benga; Mark Robert Brown as Don Linden; Davis

Roberts as Dr. Ozaba; and Garland Thompson, who was Transporter

Technician Wilson in the episode “The Enemy Within” and a crewman in the

episode “TOS: Charlie X.”

Raised in the West End

Adam

Nimoy spoke about how the series really fit his dad’s persona and

background. “The fact is, he’s a product of where he was raised, frankly

by Russian immigrant parents in the West End of Boston, my

grandparents,” he said, adding that he knew and loved Dora and Max Nimoy

dearly, visiting them each summer and during college. “I adored them,

but they were not demonstrative, as my father would say.

They were not affectionate, not loving, nurturing type of people.”

Plus,

Nimoy was born and raised in the Depression. “It was all a mindset of

hustle, hustle, hustle, hustle,” Adam Nimoy said. “That’s the whole

focus and he was, you know, selling vacuum cleaners on Boylston Street

and working at the camera shop on Tremont and at the card shop on

Bromfield and selling newspapers on Beacon Hill and on the Common. That

was his whole thing.” And not much changed when Nimoy arrived in LA. “It

was the same thing forged on the streets of Boston,” the younger Nimoy

said. “He was selling fish tanks and maintaining them, driving a cab,

scooping ice cream, working gumball machines, working at a pet shop,

selling refrigerators, selling insurance, and all the while pursuing his

career.”

Indeed, Nimoy was nearly

omnipresent on the small screen, appearing in many of TV’s golden era

shows like “Bonanza,” “Gunsmoke,” “Wagon Train,” “The Virginian,” “A Man

Called Shenandoah,” “Laramie” and “Rawhide.”

Yes, he was somewhat of a cowboy before a space explorer, but one thing was sure — he was always working.

And

then came Spock. “The primitive Spock had a rough, uneven haircut,”

Nimoy explained. What about the eyebrows, and those ears? “Many years

later, Dad explained to me that it was Charles Schram, who ran the MGM

makeup lab, who created the first latex ear prosthetics,” he said,

noting that Schram was best known for his prosthetic makeup of the

Cowardly Lion and the Wicked Witch in “The Wizard of Oz.”

Flash forward, and Leonard was in personal recovery

for his admitted drinking. “I was in recovery too, but I’m in the

program,” Adam Nimoy said. “I’m going to meetings, learning the

principles of recovery. I have a sponsor. So you know I’m doing all the

stuff.” His dad, though, was doing it solo, and so nothing changed.

“Sometimes, he could be so difficult, I would think to myself, ‘Oh my

gosh, somebody give this guy a drink!” he said, to a rare laugh from the

transfixed crowd.

Recovery

gave Adam Nimoy tools to try, especially during this very low point in

their relationship. He called his dad on his birthday, sent him a card

with a photograph of an old-fashioned milk cart, and got an email of

thanks back. “On Father’s Day, I wished him a happy Father’s Day and he

wished me one as well,” he said. “And then he informed me in an email

that our relationship had been meaningless, and sent me a letter about

all the terrible things I had done throughout our relationship.” His son

could only recoil.

But

a friend from recovery urged him to go and rectify things, and Adam

Nimoy went to his father’s house. “I walked in the door, and everything

changed,” he said. That wasn’t the only change. He stopped practicing

law, which he enjoyed — in entertainment law, he focused on music

publishing, and got permission for the band Information Society to use

“Star Trek” snippets. He and his first wife had divorced, and he became a

substitute teacher in his local high school district to be closer to

his kids. Nimoy remarried in 2011 and only four months later, his new

wife’s doctor called him with terrible news. “I called my father and

told him that Martha had terminal cancer and that the doctor had called

me. ‘Where are you?,’ he asked. ‘I’ll come to you now.’” That

conversation was unthinkable just a few years before, he said.

Adam

Nimoy became a TV director, with many major episodes of top shows to

his credit. His son is a member of the punk band The Offspring.

Adam

Nimoy was an intern for the late congressman Thomas P. “Tip” O’Neill.

In 1976, while on a tour of the Capitol with his dad, he’d met O’Neill,

who offered the younger Nimoy an internship. “I was 21 and I was there

for eight weeks working on the Hill,” Nimoy recalled.

Attendee

Tom Stocker of Boston was instrumental in establishing a Leonard Nimoy

Day observed in Boston each year on his March 26 birthday. “I wrote up

the declaration, submitted it to then-Mayor Marty Walsh, and it was

instituted,” he said.

Boston’s

Museum of Science is conducting a fundraiser for a Leonard Nimoy

memorial sculpture by David Phillips and has thus far raised $390,056

out of $500,000. “Make the logical choice: Help bring the spirit of Star

Trek to the Museum!” the page states. “We all know that Spock, and the

actor behind the character, Leonard Nimoy, believed strongly in the

importance of science, the significance of generosity, and of course the

power of logic,” it continues. “Before his death, Leonard Nimoy was

significantly involved with the Museum, growing up in the area and

narrating the original Mugar Omni Theater preshow.”

Adam

Nimoy visits his Dad’s grave at Hillside Memorial Park in Culver City,

California. “I think his spirit is still there,” he said. “He’s so

powerful. I miss him and I still want to share a lot of stuff with him,

so I do that.” He spoke of a recent tweet about one of his father’s

roles. “Half a million people looked at that tweet,” he said.

Today, in Westwood Village, not far from Nimoy’s grave, his name is emblazoned on the renovated UCLA Nimoy Theatre.