“Haiti Victorious 2” by Gloretta Baynes.

“Martin Freeman collage,” A Peculiar Freedom Series 2024, by Reginald Jackson.

“Eggs that Hatch” (Modern Maroon Wedding) by Bryan McFarlane.

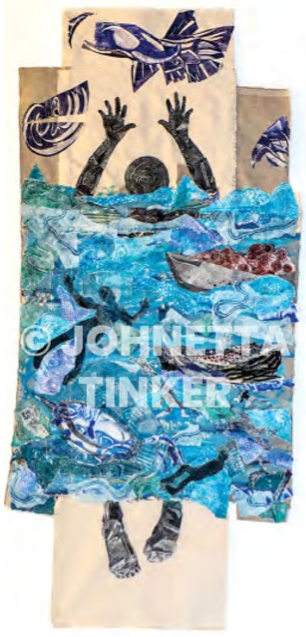

“Arriving on a Nightmare” by Johnetta Tinker.

“NUBIAN SQUARE#2” by Hakim Raquib.

(From left) L’Merchie

Frazier, moderator, Jeff Chandler, Reggie Jackson, Johnetta TInker,

Percy Fortini-Wright and Gloretta Baynes at the May 30 roundtable event.

“Orange Line with Fish” by Percy Fortini-Wright.

More than 75 Black art lovers gathered last month at AAMARP, the African American Master Artists-in-Residency Program, for an artist roundtable with the theme, “Black Art in Afro-Centric Spaces,” the second in the Banner [Virtual] Art Gallery Roundtable series. This is part one of a two-part recap.

Presented by the Bay State

Banner and AAMARP, the May 30 event at 76 Atherton St. in Jamaica Plain

featured eight of New England’s leading Black visual artists who have

been spotlighted in the Banner’s [Virtual] Art Gallery series: Larry

Pierce, Lucilda Dassardo-Cooper, Reginald “Reggie” Jackson, Gloretta

Baynes, Johnetta Tinker, Hakim Raquib, Amber Torres and Percy

Fortini-Wright.

Moderated

by Ron Mitchell, the Banner’s publisher and editor, and L’Merchie

Frazier, mixed-media artist and executive director of creative/strategic

planning at SPOKE Arts, the roundtable event paid tribute to AAMARP’s

founder, Dana C. Chandler Jr. While Chandler couldn’t attend because he

was in New Mexico, he sent his regards.

Frazier asked the artists to discuss their art, their relationship to the Black arts movement and Chandler’s influence.

Cambridge native Gloretta Baynes, whose artwork was displayed in the AAMARP gallery, spoke first.

“I

work in many different mediums. I work in textiles. I work in

photography. I do mixed media, some sculptural works and some

installation works,” she said.

“If you look to the left,” she continued, “you see ‘Haiti Victorious 1 and 2.’ That is a digital collage with lots of

different types of filters and nuances. There’s the Haitian flag

represented and the hibiscus flower. The two young people who are there

represent a new generation of leaders.”

She said the piece illustrates how young people in Haiti are surviving immense adversity.

“But

this is being shown in a very dignified manner,” Baynes added. “So,

even though their lives have been shattered due to a lot of

circumstances in Haiti, I want to show the tenacity and dignity of them

surviving earthquakes and domestic terrorism in Haiti, and that they are

going to persevere.”

Next, professor and visual artist Reggie Jackson spoke.

“I’m an artist, educator and traveler,” he said. “The

philosophy that I have come to feel very deeply about as of late is that

art is the balm and the cure for much of the trauma that we’ve

experience as people of African descent. When I think about that in

terms of the trajectory that many of us have been on, it’s kind of a

self-healing journey that one goes on, and at the same time, we’re able

to help others understand some of the things that we may have gone

through.”

He continued, “And so, I’ve begun to think that this is a little more than a calling. It’s a spiritual

journey, obviously, and one which I pursued many years ago as I began to

think about our African identity, and as I looked into how our

Africanity has transferred into these spaces that we now occupy — as I

looked at African retentions or African survivals in these Americas and

the Caribbean. And so that’s taken me to a lot of different places.”

Photographer Hakim Raquib told the story of how he came to photography “in a very strange way.” “Back in 1969, after

studies at Fisk University and the Civil Rights Movement — I was a

member of SNCC — I came to Boston and worked with Mel King and the new

Urban League,” Raquib said.

“My

career started one day when I was visiting ... the Bay State Banner ...

for the Urban League. Downstairs there was a program called the Roxbury

Photographers Training Program, which was started by MIT graduate

students. A friend of mine, an artist/photographer named Wes Williams,

came out, and I said, ‘Wow! How are you doing?’ He said, ‘Hey, what are

you doing?’ I already had a camera. So I joined this program, and that

started my career,” Raquib said.

Collage artist Johnetta Tinker recalled that Chandler knew her before she knew him, because he was a friend of her older brother.

“I

learned about Dana through my African American art history course at

Texas Southern University,” Tinker said. “That’s where I also learned

about John Biggers, Allan Crite and John Wilson, all of [whom] were in

my art history course. That’s how I learned about all the Black

artists.”

Tinker credited Chandler and AAMARP for supporting her in her career.

“When

I came to Boston, my first really exciting exhibition was here at

AAMARP. There were four women in the exhibition. Dana was in charge of

it,” she said.

Tinker

continued, “Unfortunately, my father passed away during that time and I

was going to just say, ‘I’m not going to be in the exhibition. May I

tell the young people, the work has to be done, you can’t have an

exhibition without the work being done?’ So, the work was done, and Dana

came over, got my stuff and said, ‘Oh no. You’re going to be in this

exhibition.’ So did Allan Crite. It’s the back-up of the community that

helps you get where you need to be.”

Bryan McFarlane, an

abstract and semi-abstract oil painter, was in the audience. He asked,

“To what extent should we depend on the Institute of Contemporary Art

and the Museum of Fine Arts for our developmental growth?”

Boston-based graffiti artist and painter Percy Fortini-Wright responded,

“I honestly think it’s a good idea not to depend on one institution.

It’s good to petition multiple institutions. Petition all the

institutions to put their money where their mouth is and actually do

something.”