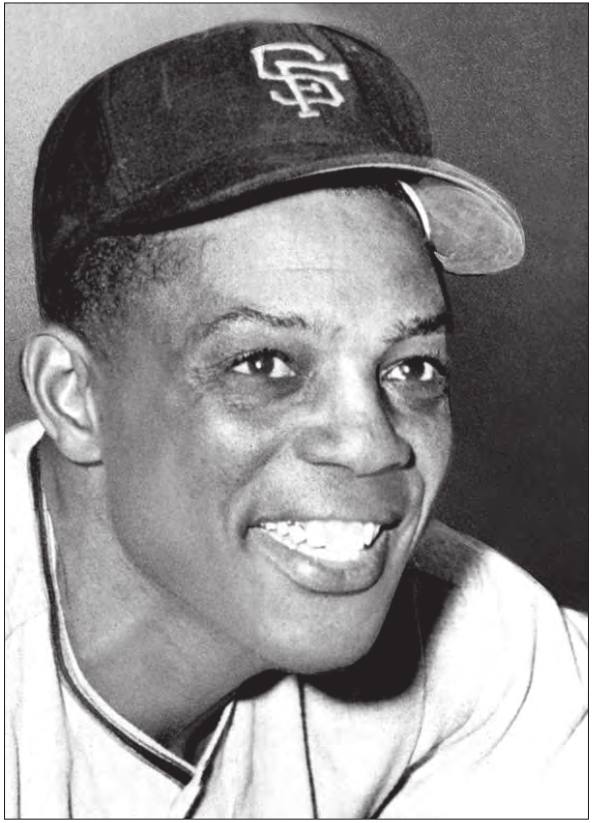

Willie Mays in 1961.

President Barack Obama

talks with baseball great Willie Mays aboard Air Force One en route to

the MLB All-Star Game in St. Louis, July 14, 2009.

The name “Willie Mays” rolls off one’s tongue with rhythmic quality and the melodic sound of great symphony music. Every time I have said his name since the days of my youth, I have thought of music produced by Beethoven, Mozart, Quincy Jones, and other great people who produced masterpieces of musical art that have stood the test of time.

William Howard Mays Jr. produced his own special brand of music on a baseball diamond. His work thrilled millions of baseball fans during his illustrious 23 years of playing Major League Baseball. His incomparable skills gained him the reputation as the “Best All-Around Player” in the history of baseball.

I first witnessed his work as an 11-year-old when I was taken to Connie Mack Stadium — the home of the Philadelphia Phillies. I sat transfixed as I watched Mays roam the vast spaces of centerfield, running down deep flyballs and turning them into outs. “Willie Mays’ glove is where triples go to die” was quoted to me so many times that I thought that it was a part of the English language. While most centerfielders ran down such balls, Willie “glided” to the spot where they would land and would use his signature “basket-catch” to record the out. His defensive work produced 12 Gold Gloves — for defensive excellence — tying him with Roberto Clemente for the most by an outfielder.

But there was so much more to this amazing athlete. He was labeled a “5-Tool Player,” one who could run, hit, hit for average and power, steal bases, and throw out opposing baserunners from the deepest parts of the outfield. And he did it all with a fluidity of style and grace all his own.

He was born May 6,1931, in Westfield, Alabama. Nicknamed the “Say Hey Kid” during his baseball playing days, Mays was a superior all-around athlete from his youth, excelling in football, basketball and other sports. But his true passion was for baseball. He joined the Birmingham Black Barons of the Negro American League in 1948, playing with them until the New York Giants signed him as a teenager in 1950.

After struggling, going hitless for his first 24 at-bats, Mays, upon receiving a vote of confidence from his manager Leo Durocher (who told Willie: “You are my everyday centerfielder whether you hit or not.”), went on to win Rookie of the Year honors in 1951. He hit 20 home runs and played an integral part in the Giants famous comeback (from 131/2 games back in August) to beat the Brooklyn Dodgers in what became

known as “The Miracle of Coogan’s Bluff.” Mays would tell me years

later: “I was on deck when Bobby Thompson hit his climactic,

pennant-winning 3-run home run off Ralph Branca” in the third and

deciding playoff game. “I was so nervous, hoping that I wouldn’t be the

one who made the last out.” He would later tell me: “That was one of the

only times I ever felt nervous in a baseball game. Thank God, for Bobby

Thompson. He took all that pressure away with one mighty swing of his

bat.”

A few years later, it was

Willie Mays’ turn to be the ultimate hero of his own story. He gained

legendary status with his magnificent over the shoulder,

backto-the-plate catch, 425 feet from home plate, to rob Vic Wertz of

extra bases. As great as the catch was, Mays was lauded for his

instinctive, reflexive, throw back to the infield, which kept two

baserunners from easily scoring and the game tied at 2-2 in the 8th

inning. The Giants would win game one of the series on a 3-run homer by

Dusty Rhodes in the 10th inning with Mays

scoring the winning run. His phenomenal catch is still considered the

greatest play in World Series history. (Historical Note of interest:

Today, the World Series Most Valuable Player Award is named in honor of

Willie Mays.

The figurine on top of the

award is that of Mays’ amazing catch.) As a result of Mays’ catch the

Giants went on to sweep the Cleveland Indians four-games-to-none to

capture the 1954 World Series — the only World Series title for Mays in

four appearances, 1951, ’54, ’62 and ’73 with the New York Mets.

Affectionately

known to his family, teammates, and friends as “Buck,” Mays fashioned a

career of statistical milestones which included 660 home runs. He was

ranked third when he retired, sixth as of February 2024, a lifetime

batting average of .301 with 3,293 hits and 2062 runs scored. He ranked

seventh all time, batted in 1909 runs - and ranked 11th as of this year.

Mays stole 338 bases and is deep in the All-Star Game record books with

24 appearances —second only to Hank Aaron’s 25. His defensive

brilliance is displayed by his 7,095 outfield putouts, which is still

Major League Baseball’s alltime mark. He would win the National League

Most Valuable Player Award in 1954 and ’65 and All-Star Game MVP Awards

in 1963 and ’68.

I

witnessed much of the Willie Mays magic as a young person and later as a

sportscaster. During interviews with him over the course of many years,

I learned a lot about the game of baseball and his drive for success in

the game. One of the criticisms of Willie Mays was that he remained

silent on racial issues, refraining from public complaints about

discriminatory practices that affected him. There are also those who

will point to his two divorces, money problems and other issues in his

life.

But none of

these off-field issues clouded the on-field wizardry of the man named

Willie Mays, who achieved such greatness despite medical maladies like

his fainting spells, which hospitalized him multiple times.

Mays

was a first ballot inductee into Major League Baseball’s Hall of Fame

(1979) and a recipient of the United States Presidential Medal of

Freedom Award, presented by President Barack Obama in 2015, a highlight

of his lifetime resume. His death on June 18, 2024, came just two days

before Major League Baseball was to honor him as one of only three

living members from the Negro Baseball League (1920-1948). It was

fitting that the game was played at Rickwood Field in Alabama, the

oldest ballpark in America, which opened in 1910. The game was dedicated

to the memory of Wille Howard Mays Jr., whose professional baseball

career began on that field.

Eternally rest Willie Mays — the greatest all-around baseball player these eyes have ever seen.