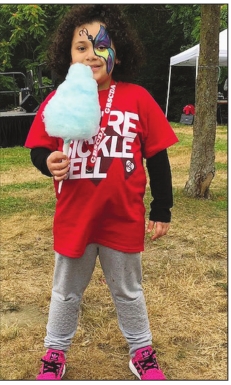

Jalyssa Batista-Juarez, 12, was diagnosed at birth with the SS genotype of sickle cell disease.

Jalyssa Batista-Juarez, 12, was diagnosed at birth with the SS genotype of sickle cell disease.

Carissa Juarez knew she was a silent carrier of the sickle cell trait. But when her newborn daughter, Jalyssa Batista-Juarez, was diagnosed with the SS genotype of sickle cell, a severe form of the disease, Juarez’s relationship with the illness transformed.

Unfamiliar with what it took to care for a chronically ill child, Juarez began researching the disease and embraced the role of caregiver along with that of mother. Soon after, she leaned into advocacy work in her community and in the Massachusetts State House, spreading the word about the disease not just for her daughter, but for others living with it and their caregivers.

“I just said, ‘Hey, you know what? I’m so into this, my heart is dedicated to this. This is what I’m gonna do,’” said the Hyde Park native.

When Batista-Juarez was just three months old, Juarez connected with the Massachusetts Sickle Cell Association, which provided her with resources and supported her. Now, she’s an ambassador for the Dorchester-based organization, which is among a group of 46 nonprofits across the country that this week will come together to raise awareness for sickle cell disease.

June 19 is World Sickle Cell Awareness Day. Through a movement called “Shine a Light on Sickle Cell,” now in its sixth year, nonprofits and community organizations are set to host activities in their communities to get the word out about the disease.

Several cities, mainly across the northeast, will illuminate the facades of some of their buildings in red, a color that symbolizes the disease, to campaign for universal care. Here in Boston, City Hall is set to be illuminated in red.

In the U.S., sickle cell disease, characterized by misshapen blood cells, affects over 100,000 people, an estimated 90 percent of them Black or African American, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The disease occurs in one in every 365 Black or African American births in the U.S. Across the globe, millions of people with sickle cell disease confront health complications such as anemia and acute and chronic pain. Even so, advocates say sickle cell disease hasn’t received the warranted attention.

“This is a disease that has been pushed aside and nobody really speaks about it. And there’s not much being done for it. And I think there needs to be more out there, and we need to speak about it more. And we need more funds,” Juarez said.

Caregivers, she added, need more help, too. “We also need somebody to put our head on…because it is a lot.”

Many of the challenges sickle cell patients and their caregivers face remain in obscurity, Juarez said. For many sickle cell patients, life is a revolving door of medical emergencies.

Since she was born, Batista-Juarez has required hospitalizations every other month. This put a strain on the family when Juarez, a single mom of five, had to quit her job to take care of her daughter. The disease has also impacted the family dynamic, with Juarez unable to devote as much time to her other children or to partake in many family activities.

“Not only did it affect me as the caregiver, but overall, her siblings and her family because we just want to take her pain away,” Juarez said. “And we can’t do that, you know, and we hate to see her going through that.”

“Shine a Light on Sickle Cell” is just one of the ways that organizations are lifting the veil off what it’s like to live with sickle cell disease and care for someone who has it.

For the last 29 years, the Massachusetts Sickle Cell Association, a volunteer-run organization, has supported and advocated for sickle cell patients and their families, aiming to improve the quality of life of the people it serves and to increase access to care.

Jacqueline Haley, the organization’s executive director, said a lesser-known aspect of living with sickle cell is its all-consuming effects.

“We have warriors who have gone to school, gone through college, trying to achieve their dreams and have to abandon these dreams because of the disease,” she said.

She knows people as young as 20 who have had to have hip replacements due to sickle cell. For others, the disease affects their eyes, liver, arms, and other body parts.

In her lifetime, Juarez’s daughter has been hospitalized over 400 times, Juarez said, and has undergone a laundry list of operations, including ones to her gallbladder, spleen and tonsils. This year alone, the 12-year-old has missed 152 days of school.

Every day is unpredictable. What may begin as a good morning can quickly warp into a serious health crisis, Juarez said. Beyond the social and familial consequences, these experiences place a hefty financial burden on families who already deal with barriers to accessing treatment.

“Equity in care is an issue for our patients,” Haley said, adding that some patients “face discrimination when they go into the ER” or enter a facility that is unfamiliar with sickle cell disease. The level of care also varies greatly depending on location.

A bill proposed by the Massachusetts Sickle Cell Association that would improve sickle cell care is currently under review in the Massachusetts State House, Haley said. If passed, the bill would establish a standard of care across the state for sickle cell patients.

“As an organization, our goal is to create systemic changes, to remove these barriers, to increase access to these resources,” she said. “So if our patient goes to Fall River, if you go to Cape Cod, if you come to Boston, your care should always look the same,” she added.

On June 27, as part of “Shine a Light on Sickle Cell,” the Massachusetts Sickle Cell Association will host a webinar about post-hospital crisis care. The event will educate attendees on the post-hospital adjustment for both sickle cell patients and their caregivers.

Juarez has been a sickle cell caregiver and advocate for over a decade now and said people around her have thanked her for her work. Some patients have difficulty fighting for themselves because of the physical pain they experience.

When Juarez steps in, she said, people often tell her that they wish they had a caregiver like her by their side.

Juarez simply wants to “put a smile on their faces, to show them that I care,” she said. “I don’t have the disease, but I care. Not just because it’s my daughter, but I care for all of you. Because I understand now what this disease does, and I’m here, and I’m going to keep fighting and advocating for the sickle cell community.”