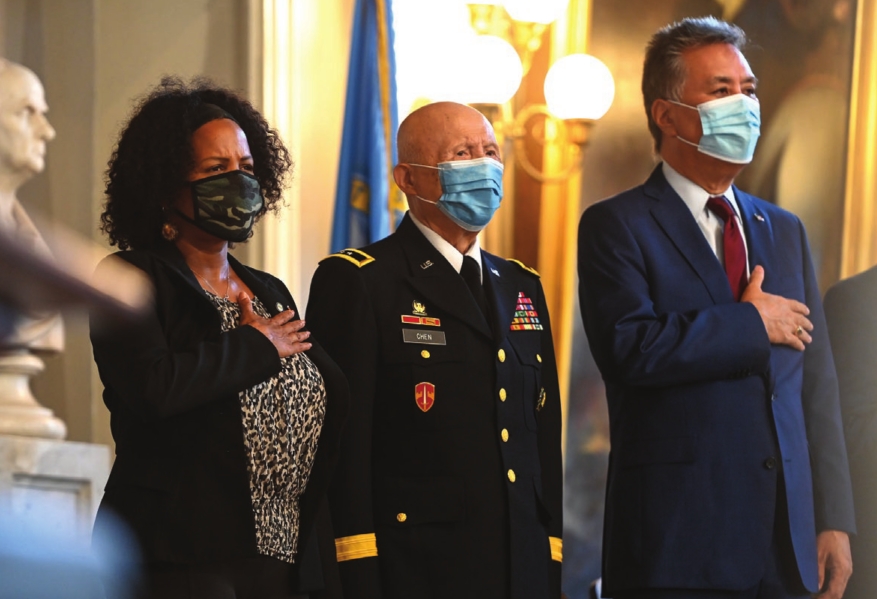

Mayor Kim Janey attended the Congressional Gold Medal Ceremony for Chinese Americans who served during WWII.

Diesel buses turn onto Dudley Street.

A call for relief in communities plagued by poor air quality

As organizations across the state are looking to shift practices and models to become more climate-friendly, the MBTA is planning a shift to a fully electric bus fleet. The agency proposes a fully electrified fleet by 2040, but some transit activists and state legislators say the shift should come sooner and should have a stronger focus on the communities most impacted by air pollution.

The MBTA’s plan, which was outlined in an April report to the organization’s Fiscal and Management Control Board would work to update infrastructure in bus yards and replace the existing fleet — largely composed of diesel-electric hybrid and compact natural gas buses — with all electric battery-powered buses.

The first steps of the plan include constructing a new facility in Quincy, as the current one lacks quick fixes that could make it suitable to house electric battery-powered buses. The plan also describes $21 million of renovations to the North Cambridge bus yard, which houses much of the MBTA’s electric trolley bus fleet.

However, some activists, like Jarred Johnson, executive director of

the group TransitMatters, said that removing the trolley buses is the

wrong first move, as they are already electric. These buses, which run

on routes 71 and 73 through Cambridge and Watertown, pull their power

from wires that hang over the street and operate without diesel or

natural gas.

In an

analysis released in September comparing the trolley buses with

battery-powered electric buses, the MBTA cited safety concerns with the

wires snapping or maintenance crew having to work in the street to do

repairs. But Johnson said that he thinks the system, which in the middle

of the 1900s was widespread across the city, is reliable.

“We

would acknowledge that those buses have been on the road for some time —

though, I think the fact that they’ve been on the road for a long time

tells us about just how reliable and how useful that technology is,”

Johnson said.

An environmental justice focus

Activists

also suggest the first steps in removing diesel pollution from the bus

fleet should be in communities that experience greater impact from air

pollution.

“One of the

big issues for us is that [first,] it doesn’t actually have any

emissions benefit because those buses are already electric,” Johnson

said. “And then, secondly, there are [environmental justice] communities

that have been asking for cleaner buses for a long time.”

Those

environmental justice (EJ) communities are places like Dorchester,

Mattapan, Chelsea and Lynn, among others, that are comprised of largely

disadvantaged populations at greater risk from environmental hazards.

Mela

Bush-Miles, transit-oriented development director at Alternatives for

Community and Environment and head of that organization’s T Riders

Union, is a Roxbury resident who said she has seen the impact from the

use of non-renewable fuel sources in MBTA buses, especially with the bus

depot at Nubian Square near where she lives.

“All

of these buses going in and out and concentrating diesel exhaust if

they’re idling or whatever, it brings a lot of air pollution and it’s

causing harm to our communities,” Bush-Miles said.

Her three children, now adults, have asthma, and Bush-Miles said they’re still seeing the impacts of breathing struggles.

“We

need our climate to be breathable, we need our air to be breathable,

and we have enough trucks and cars driving around through the community

that we don’t need something to compound the problem,” Bush-Miles said.

For

Justin Ren, a researcher at Boston University who has focused on

electric vehicles, in principle, it doesn’t make sense to pull the

trolley buses before adding battery electric buses elsewhere. However,

whether those trolley buses stick around in the long term is “the

million-dollar question.”

After

pointing out examples of several cities that have embraced trolley

buses with success, Ren said it ultimately depends on the state of the

infrastructure and where priorities lie.

“You

have to really look at, ‘OK, I have a million dollars, where should I

spend it? Do I upgrade the system? Do I replace the system?’ This is

where things get really, really difficult,” Ren said.

Johnson

is a proponent of the MBTA considering in-motion charging technology,

an updated form of the trolley bus system that allows it to not only run

on its overhead wire system, but to use that system to charge batteries

that would also allow it to run off-wire.

The

MBTA, in a comment to the Banner, didn’t say if it is considering that

technology, but did point out that the transit agencies opting to

reinvest in their trolley bus system are those that have an extensive

system in the first place. According to representatives from the MBTA,

there are fewer than 20 miles of overhead wires in the Greater Boston

area. According to a roster of MBTA vehicles from the Boston Street

Railway Association, 28 of the 1,148 buses in the MBTA fleet — or about

2.4% — are electric trolley buses.

Johnson

said he objects to what he sees at the MBTA’s move to insist on making a

standardized fleet. But for Ren, a fleet with a single type of

electrification technology is ideal.

“You don’t want to have a hodgepodge of different systems; you want to simplify,” Ren said.

State-level discussions

In

the State House, the conversation is continuing on another front. A

bill presented by Representatives Christine Barber, who serves the 34th

Middlesex District, and Steven Owens, who serves the 29th Middlesex

District, would push the MBTA to electrify its bus fleet by 2030. Across

the state, other regional transit authorities would have to electrify

by 2040.

“We all know

climate change is something we need to address yesterday and do all that

we can to stop the temperature of our communities from increasing,”

Barber said, citing worse health outcomes in parts of her district most

impacted by transportation-related air pollution.

In

addition to the early deadline to electrify the MBTA fleet, the bill

would focus electrification efforts in EJ communities sooner, by 2025.

“I

want to make sure it’s not just Cambridge and Watertown that are

getting electric vehicles, but that we’re looking at Roxbury,

Dorchester, Lynn, Chelsea — communities where lots of people take the

bus and buses make up a huge amount of the pollution in their

communities,” Barber said.

Despite

ongoing concerns about the state of funding for the MBTA, Barber said

it’s important that the transit agency, which she referred to as “a

public good,” continues to receive the money it needs to keep operating,

and that funding allows the MBTA to move toward cleaner power sources.

“It

is an incredibly important part of our economy, it runs the economic

engine of the Boston metro area, so we need to be investing in the MBTA,

but specifically in electrification and invest in climate change

[action] for communities that have borne the brunt of climate change for

many years,” Barber said.

She

pointed to the Fair Share Amendment — a ballot question that will

appear on the 2022 state ballot and would implement an additional tax of

4 percentage points on any annual income over $1 million — and federal

funding as possible avenues to keep funding the MBTA and its

electrification efforts.

She

also said that, while 2030 is less than a decade away and there has

been no logged action regarding the bill since it was referred to the

committee on transportation in March, she feels 2030 is a reasonable

goal for full electrification of the bus fleet.

“Because

of the amount of use of MBTA buses, they do turn over their fleet and

purchase new vehicles fairly frequently and it’s doable,” Barber said.

Winter challenges

A

potential challenge to a full fleet of battery electric buses: They

face challenges in cold weather as the batteries struggle in the cold

weather.

“Just like your iPhone doesn’t work well in sub-zero temperature, or the battery suddenly dies, it’s the same thing,” Ren said.

According

to a 2019 study from the Center for Transportation and the Environment,

battery electric buses could experience a loss of about 32.1%

efficiency when the temperature drops from the range of 50 to 60 degrees

to a range of 22 to 32 degrees.

In

a 2020 report from the MBTA, battery electric buses with a maximum

range of 110 miles at 70 degrees dropped by nearly half, to a maximum

range of 60 miles, at 20 degrees.

But

Barber said she’s confident the technology will be able to stand up to

Boston’s winters, citing cities like New York and Chicago with similar

climates also working toward electrification.

Some

solutions currently exist, like in-route charging stations that top off

the batteries at certain bus stations or heaters that warm the battery

and keep them running at higher performance. However, the charging

stations require greater investment in infrastructure, and placement

works best in shared bus corridors, limiting their effectiveness on

routes that don’t share much ground. The heaters are often diesel,

reintroducing some level of air pollution.

Ren,

however, said the technology is improving and that expecting it to be

able to support a full bus network is “more than just hope.” He said he

believes within a few years the technology will be there.

For

activists like Bush-Miles, while the details of how are important, the

most important part is getting new electric buses out onto the road.

“We’re

just trying to live a few more years and have a better quality of

life,” Bush-Miles said. “Those electric buses can be part of the

equation that can help us get there.”