Boston School Superintendent Tommy Chang announced

he is leaving by mutual agreement with Mayor Martin Walsh three years

into his five-year contract.

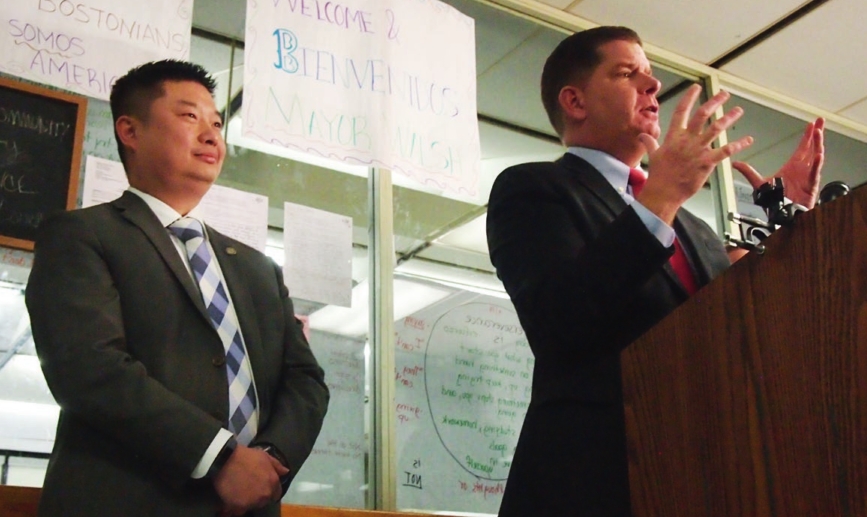

Outgoing BPS Superintendent Tommy Chang and Mayor Martin Walsh at a January press conference.

Tenure marked by clashes with parents, many not his making

When Boston Public Schools Superintendent Tommy Chang announced Friday he is stepping down three years into his five-year contract with the city, the news was sudden, but the warning signs were there.

Chang has led the schools during a time of frequent clashes with teachers, parents and students over issues ranging from changing school start times to school budget cuts, often taking the flack for decisions made in City Hall.

His abrupt departure comes on the heels of a lawsuit filed by a coalition of rights groups against Chang for his apparent refusal to disclose how much information the department shares with federal immigration officials.

The immigration controversy underscores the complex political dynamics at work in the Boston superintendent’s job. The rights groups’ push for the information began when Boston Police officers stationed at East Boston High School in 2017 filed an incident report alleging a student who was involved in a confrontation at the school was a gang member. The student, who insists he was not in a gang, was subsequently detained by ICE for nine months before being deported.

Ivan Espinoza-Madrigal, executive director of the Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights and Economic Justice, emphasized that the lawsuit filed was never about Chang.

“We

never asserted that the Superintendent personally proffered these

records to ICE,” he said in a press statement Monday. “It is the City of

Boston’s policies and practices that are at issue.”

The

incident was emblematic of the challenges facing Chang. While the

political dynamics that have sparked controversy often involved factors

beyond his control, Chang’s position as the public face of the school

system have frequently made him a target for fire from the public and

from within City Hall.

In

a statement to news media released last week, Walsh fired a parting

shot, implying that Chang was unable to advance his administration’s

agenda for the schools.

“In

order to successfully implement our education agenda, we need a

long-term education leader with a proven record in management who can

gain the confidence of the community on the strategic vision for the

district and execute on the many initiatives that have been identified

as priorities for our students and schools,” the mayor’s statement read.

But

much of the conflict between parents and BPS over the three years of

Chang’s truncated tenure in Boston pre-dated his tenure. In December of

2015, just months after Chang took the reins at BPS, the city released a

draft of a report it commissioned from the global consulting group

McKinsey & Company, that alleged the district had a surplus of

36,000 seats and recommended school closures and consolidation. The

report, widely panned for using cafeteria, hallway and gymnasium space

to calculate usable square footage of school buildings, stoked fears

that the district was looking to offload buildings to charter school

operators.

The

following year, as the Walsh administration advanced a school budget

that saw more than half of the district’s schools receiving funding

cuts, Chang was frontand-center, giving justifications for the cuts.

Parents, teachers and students, cognizant that the mayor controls the

purse strings, picketed Walsh’s State of the City address, and students

staged two citywide walk-outs and multiple protests of cuts to their

schools.

One unpopular

decision that landed squarely on Chang’s shoulders was his initiative

last December to change school start times. While the idea stemmed from

parent pressure to create later start times for sleep-starved high

school students, the announced new schedules became a lightning rod for

parent activists across the city who were outraged that the BPS plan

would have increased the overall number of elementary school students

starting class earlier than 8 a.m. and led to some schools letting out

as early as 1:15 p.m. in the afternoon. While Walsh initially stood by

the plan, he eventually pulled the plug on the idea days after a group

of angry parents confronted him during a Christmas tree lighting

celebration in West Roxbury.

Among

the more befuddling controversies Chang took the blame for was an IRS

audit of City of Boston payroll records that found that BPS principals

had misallocated school activity funds to pay staff for services such as

proctoring exams. The practice far predated Chang’s tenure, and

principals were trained in proper use of the funds as soon as Chang

learned of the misallocations.

While

Walsh expressed frustration with Chang and said the superintendent did

not inform him of the audit findings, the same audit turned up far more

extensive payroll errors inside City Hall, including failures to deduct

Medicare and payroll taxes. In all, the city was fined $944,000, just

$32,000 of which stemmed from the BPS errors. Walsh’s public rebuke of

Chang came weeks after a city official quietly handed off a check to the

IRS on Nov. 2 — the same day Walsh was on the ballot for re-election.

Other

controversies that have confused and angered parents included the

dead-in-the-water unified enrollment plan and the legislation Walsh

filed that would have made it possible — neither which had much to do

with Chang.

Chang’s

departure will not likely provide much reassurance to parents concerned

about the budget cuts and school consolidation schemes that have

emanated from Walsh. The mayor’s $1 billion Build BPS program, through

which he aims to repair, reconstruct and reconfigure many of the city’s

126 school buildings, is run out of City Hall, not in the Bolling

Building. In the coming months, an interim superintendent may likely

revisit some of the more controversial decisions while the city searches

for Chang’s replacement.

For

his part, Chang said he was proud of the work he’s done in the Boston

schools, citing a 4 percent decrease in the dropout rate, decreased

suspensions, an increase in the number of level 1 and 2 schools and his

efforts to close the achievement gap in the district.

“On

the Nation’s Report Card, in numerous areas, Boston has been one of

only a handful of districts that have made progress,” he said in a

statement sent to the news media. “Gaps of achievement and opportunity

have begun to close. That’s a credit to our teachers, principals, staff,

and families — and I’m proud of it. But no one can or should be

satisfied with where we stand, and with some crucial building blocks in

place, the time will never be better for the next leader to take the

helm.”