Photographs reveal Worcester’s historic African American community

Union victory in the Civil War liberated African Americans from slavery, but soon after, Ku Klux Klan violence and Jim Crow laws imposed new shackles on them. As the war ended, Worcester, Massachusetts was a welcoming city to former slaves seeking jobs and better lives. Although economic opportunities didn’t last — an influx of European workers got the good factory jobs, keeping most people of color in service occupations — migrants from the South built strong and lively neighborhoods in Worcester, including the ethnically diverse community of Beaver Brook.

Union victory in the Civil War liberated African Americans from slavery, but soon after, Ku Klux Klan violence and Jim Crow laws imposed new shackles on them. As the war ended, Worcester, Massachusetts was a welcoming city to former slaves seeking jobs and better lives. Although economic opportunities didn’t last — an influx of European workers got the good factory jobs, keeping most people of color in service occupations — migrants from the South built strong and lively neighborhoods in Worcester, including the ethnically diverse community of Beaver Brook.

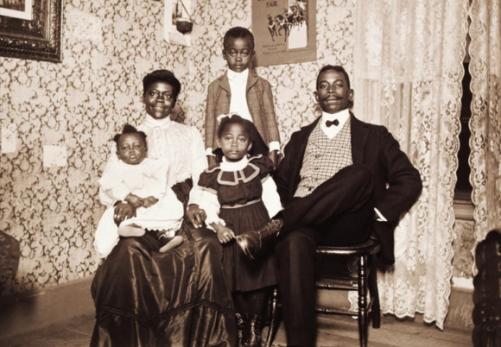

William Bullard (1876-1918), a white Yankee resident of Beaver Brook, took portraits of his neighbors over 20 years, from 1897 to 1917, amassing more than 5,400 gelatin silver dry plate negatives. Although he had no studio or professional affiliations, he rendered his subjects with great skill and painstakingly etched tiny numbers on the negatives that matched entries in his ledger, noting the names and locations of his subjects. Portraying working-class people of color with the skill and dignity reserved at that time for wealthy clients, his portraits show his subjects in their homes, on their porches, at work and at leisure. In his portraits, they are at ease and in charge.

Most homes in Beaver Brook are gone, razed in the 1950s by industrialists who bought properties and then abandoned them as empty lots. Thanks to Bullard, a record survives of people of color claiming their rightful place in society.

“Rediscovering

an American Community of Color: The Photographs of William Bullard,

1897–1917,” an exhibition on view through Feb. 25 at the Worcester Art

Museum, presents 83 of Bullard’s portraits. Rendered under the museum’s

supervision as archival inkjet prints in 2016 by John Marcy of 21st

Editions, South Dennis, Massachusetts, Bullard’s portraits tell stories

of individual and family histories, a community, a city and a nation

built from migrants who move great distances to create new and better

lives.

Co-curated by

Nancy Kathryn Burns, the museum’s associate curator of prints, drawings

and photographs, and Janette Thomas Greenwood, professor of history at

Clark University, the exhibition is accompanied by a website hosted by

Clark University (www.bullardphotos. org) and a fine catalog that

includes essays by Burns, Greenwood and Frank J. Morrill, owner of the

negatives, along with high-quality reproductions of the 83 photographs.

Nearly lost

The

exhibition almost didn’t happen. After Bullard’s death in 1918, his

brother stored the glass negatives and ledger for 40 years and

eventually sold them to his postman. In 2003, Frank J. Morrill, a

collector, purchased the materials from the postman’s grandson. A decade

later, he and his granddaughter, Hannah, then age 10, explored the

negatives to create a pictorial history of Worcester. Among Bullard’s

streetscapes, Hannah found a portrait and noticed its tiny number.

Morrill saw that it corresponded with an entry in Bullard’s logbook, and

discovered similar entries for 230 portraits of people of color among

Bullard’s negatives.

A

retired history teacher, Morrill brought the collection to the

attention of Greenwood, author of a 2009 study of the same population,

“First Fruits of Freedom:

The

Migration of Former Slaves and Their Search for Equality in Worcester,

Massachusetts, 1862-1900.” Their meeting set in motion a collaboration

between the art museum and the university that led to the exhibition.

Greenwood’s

students took part in genealogical research, studying public records

and interviewing relatives to gather biographical information on the

subjects and their heirs. Envisioning the exhibition as a

community-building experience, the museum and Clark formed an advisory

board of past and current residents. The day before the Oct. 14 opening,

community advisors and portrait subjects’ descendants from far and near

attended a celebration. At the opening, descendants of David T. Oswell,

a prominent musician, composer and teacher photographed with his viola

by Bullard in 1900, performed Oswell’s music.

The

exhibition occupies a central hall and adjoining galleries. By the

entrance is a map of the Beaver Brook neighborhood (circa 1911), a

lopsided square mile or so that today retains a small park and the

still-active John Street Baptist Church. Among its few remaining houses

is Bullard’s former home at 5 Maple Tree Lane (formerly Mayfield

Street).

An intimate

atmosphere prevails in the galleries, where the prints are framed in

gilded wood and displayed on deep magenta walls in uncluttered, thematic

groupings. A table and chairs invite visitors to browse the catalog and

related texts, including the iconic 1903 book, “The Souls of Black

Folk,” a collection of essays by W. E. B. Du Bois (1868- 1963), a leader

of the Harlem Renaissance, who advocated photography as a tool to

promote his era’s emerging black middle class. He presented a set of

photographic portraits showing elite African-Americans at the Paris

Exposition in 1900, but the subjects were mainly nameless except for a

few individuals of great renown.

Bullard

names his subjects, and, counter to studio practices of his time, which

sought to lighten black skin, he skillfully adjusts his lighting and

settings to render his subjects’ natural skin tones. Producing glass

negatives ranging in size from 3 ¼-by-3 ¼ inches to 8-by-10 inches,

Bullard worked with a bellows camera constructed of wood and leather

that took minutes to complete exposures. The process required the

collaboration of sitters, who had to remain still. Unlike studio

photographers, who favored formal poses with props and a

then-fashionable Pictorialist style, Bullard portrayed his subjects at

work, at leisure and at home.

Bullard

lacked a studio and perhaps was self-taught, but he had a knack for

rendering character and personality, a keen eye for telling details and

composition, and a warm rapport with his subjects. His portrait sitters

appear confident and well dressed, whether in leisure finery, military

uniforms or work attire.

Family and community ties

Most

African American residents of Beaver Brook came from northern and

eastern Virginia, New Bern in North Carolina and Camden in South

Carolina, where during the Civil War they came to know white soldiers,

ministers and teachers from Worcester who opposed slavery. After the

war, these white northerners helped the newly emancipated slaves migrate

to Worcester. The newcomers then helped their relatives join them in

Beaver Brook.

Southern

ties remained strong among the transplanted families. Edward Perkins,

from Camden, and his wife Celia, both former slaves, arrived in 1879.

Bullard took 36 photos of their extended family. A 1901 portrait shows

Martha (Patsy) Perkins in a stylish white lace dress with matching

“picture hat,” and another portrays her brother Ike in a top hat. When

the siblings died, their family buried them back in Camden. Bullard’s

“Edward Perkins in His Garden” (about 1902) shows Perkins posing in his

thriving garden of collard greens.

Quoted

in nearby wall text, contemporary descendant Kim Perkins Hampton says,

“Seeing the photographs of my ancestors was like looking into a mirror

for the first time. Because of this country’s bloodied past relationship

with people of color, more specifically black people, it’s extremely

rare for African Americans today to trace back their ancestry — let

alone have the privilege to see them.”

“Rose

Perkins Posing with Bicycle” (1900) shows the young laundress in

up-to-the-minute cycling attire, including a smart cap, a culotte-style

“divided skirt,” and a bouffant-sleeved blouse.

Cycling

was a nationwide craze, and Worcester was an epicenter, with a dozen

bicycle manufacturers and a host of cycling clubs including the black

Albion Cycling Club. Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor (1878-1932), who

broke racial barriers and won the 1899 world championship in cycling,

relocated to Worcester and was a devoted member of the John Street

Baptist Church.

Bullard’s

portrayals of subjects in work settings include “Portrait of Eugene

Shepard, Sr., Seated in a Railcar” (about 1905), which frames the

uniformed railcar cleaner with a long angular view of the entire

railcar, its row of ornate ceiling lights, horizontal chair backs and

vertical windows converging on Shepard, who gazes at the viewer with a

proprietor’s pride.

Ill and bereft after the death of his mother, William Bullard committed suicide at age 42.

Little

known outside of his community and family, Bullard left a powerful

legacy shared with the world in this exhibition. Bullard’s photographs

tell a story of individuals and families that is also the nation’s story

— of a people moving from slavery to freedom and full citizenship.

Their stories might have been lost. Countering the eradication of family

and individual historical records imposed by slavery, Bullard’s

portraits keep these histories alive.

ON THE WEB

Worcester Art Museum: www.worcesterart.org

“Rediscovering an American Community of Color” — accompanying website hosted by Clark University: www.bullardphotos.org